On Tuesday, May 2, 2023, the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project hosted the webinar launch of its new report, “Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery: Guaranteeing Sustainable Development.”

By Amanda Brown

The DRGR Project is a collaboration between the Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP) Center, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London that argues it is time for comprehensive debt reform. Utilizing rigorous research, the DRGR Project seeks to develop systemic approaches to both resolve the debt crisis and advance a just transition to a sustainable, low-carbon economy in partnership with policymakers, thought leaders and civil society around the world.

María Fernanda Espinosa, politician, diplomat and human rights advocate, moderated the discussion. The event featured five of the seven DRGR Project co-chairs: Shamshad Akhtar, Former Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan and Finance Minister of Pakistan; Kevin P. Gallagher, Director of the Boston University GDP Center; Jörg Haas, Head of the Globalisation and Transformation Division at Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung; Ulrich Volz, Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London; and Anzetse Were, Senior Economist at Financial Sector Deepening Kenya. One of the report’s coauthors, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Assistant Director of the Global Economic Governance at the GDP Center, also joined the discussion.

Following a welcome from María Fernanda Espinosa, Kevin P. Gallagher presented an overview of the report, which analyzes new data on the level and composition of public and private external sovereign debt for emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Gallagher emphasized that EMDE external debt levels and service payments have more than doubled since the 2008 financial crisis. The report also estimates that more than $812 billion in debt needs to be restructured for 61 EMDEs in or at high risk of debt distress to achieve debt sustainability and put them on a path towards meeting their development and climate goals. Many of these 61 countries, termed “New Common Framework Countries” by the project, are highly climate vulnerable.

Gallagher emphasized that this is a “now or never” moment, and that the current Group of 20 (G20) Common Framework falls short in three key areas: it leaves out middle-income countries, like Suriname and Sri Lanka, that need debt relief; it has yet to compel all creditors to the negotiating table; and it has not linked debt relief to climate and development goals.

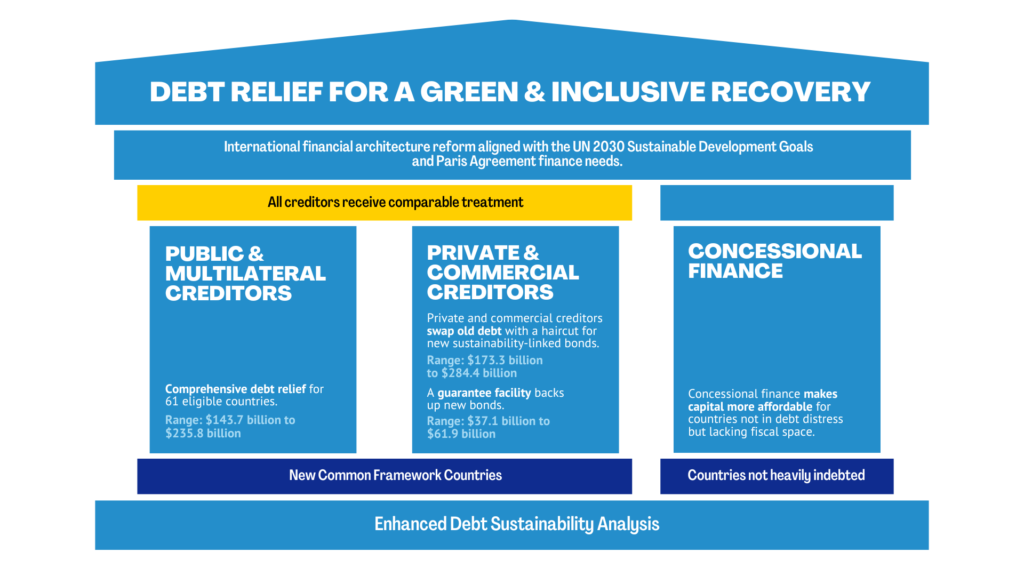

To that end, the DRGR Project has developed a proposal that is in many ways a modern-day version of the Brady Plan and the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative of the 1990s combined. The proposal consists of three pillars, underscored by necessary reform of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Debt Sustainability Analyses (DSAs). For countries in debt distress, the proposal has two pillars where both public and multilateral creditors as well as private and commercial creditors receive comparable treatment. The final pillar ensures credit enhancement for countries who do not need debt restructuring but still lack fiscal space to pursue shared development and climate change goals. Gallagher emphasized that this proposal is not a one-size-fits-all approach, nor is it a substitute for a comprehensive, treaty-based approach to debt reform.

Following this overview, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary highlighted key figures from the report, laying out the context of an overlapping debt and development crisis. He first examined the composition of developing country data stock from 2008-2021, showing that the share of bondholders has been the most prominent change, as they are now one of the largest creditors. Bhandary also emphasized how an increasing cost of capital has made it challenging for EMDEs to make investments – if the returns on those investments are lower than the cost of capital, they would only add to the debt burden. The data also reflects how countries that are more climate vulnerable are also more likely to have lower sovereign borrowing space, compounding their ability to effectively respond to climate shocks and make necessary investments for adaptation and resilience. In addition to debt workouts, the “New Common Framework Countries” urgently need at least $30 billion in immediate debt relief, which would also incentivize creditors to participate in debt negotiations and reduce short-term payment distress.

Next, Ulrich Volz elaborated on the DRGR proposal. He emphasized the need for improved DSAs to include adaptation and mitigation, climate risk and other critical spending needs. He also underscored Gallagher’s point that the proposal is one piece of a much larger reform agenda. Volz focused on the private and commercial creditors pillar, explaining a system of carrots and sticks to ensure private sector participation in debt restructuring. The carrots consist of a guarantee facility to unlock large-scale debt restructuring, and sticks could take the form of immediate debt service suspension to put pressure on private creditors. Even with an ambitious, HIPC-like debt restructuring, Volz noted that a tremendous $1.26 trillion gap would still need to be financed to prevent a “lost decade” of inaction towards achieving shared climate and development goals.

To close out the presentations, Anzetse Were provided a view from Africa on reforming the financial architecture for debt relief. She explained the connection between the debt crisis and climate change in Africa, where climate change has impacted fiscal strength and space as governments face increased expenditures from droughts, floods and extreme weather events. Were described how the fiscal strain then prevents African governments from using expenditures for development and other productive matters as they are focused on fixing the impacts of climate change instead. As a result, African governments have lower repayment capabilities in both local and foreign currencies. Were emphasized that the DRGR proposal is about “environmental fairness” in acknowledging both that African governments are shouldering the effects of climate change as well as allowing these governments to be honest about the impacts of climate change without being penalized by markets.

The Q&A portion of the webinar raised questions about next steps in advancing the DRGR proposal, foreign aid and climate investment, the upcoming Summit for a New Global Financial Pact in June and how to guide investment in green and inclusive areas. Gallagher called on the Indian G20 presidency to rise to the occasion in reforming the Common Framework, both to open it to all countries in debt distress and to link it to climate and development goals. Were emphasized the benefits of focusing on financial architecture in project development, and Volz pointed to the need for non-commercial investments. Shamshad Akhtar provided perspective on the debt crisis in Pakistan, discussing how Pakistan has opted not to go for debt restructuring. Finally, Gallagher explained how the June Summit will focus on many of the critical elements of the DRGR proposal, especially the rising cost of capital for mitigation and adaptation.

Shamshad Akhtar offered closing remarks, addressing her first point to those who do not think debt distress is as severe as it used to be. Akhtar pointed to the soaring public debt during the COVID-19 pandemic, deepening EMDE debt distress and the challenge of back-to-back crises. She emphasized the connection between climate vulnerability and debt distress, with a focus on the just transition as a critical anchor for the DRGR proposal. She also underscored the need for reform of the G20 Common Framework with more capacity to close the finance gap. In all, the DRGR report is a critical contribution to the discussion around debt relief, climate and development.