On Tuesday, May 14, 2024, the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project hosted a webinar discussion to launch its new report, “Defaulting on Development and Climate – Debt Sustainability and the Race for the 2030 Agenda and Paris Agreement.”

By Arabella Wintermayr

María Fernanda Espinosa, a politician, diplomat, and human rights advocate currently serving as President of Cities Alliance and Executive Director of Global Women Leaders for Change and Inclusion, moderated the discussion. Alongside Espinosa, the webinar featured DRGR Project Co-Chairs Shamshad Akhtar, Former Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan and Finance Minister of Pakistan; Jörg Haas, Head of the Globalisation and Transformation Division at the Heinrich Böll Foundation; Bogolo Kenewendo, Former Minister of Investment, Trade and Industry of Botswana and Former Special Advisor to the United Nations Climate Change High-Level Champions; Patrick Njoroge, Former Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya; and Ulrich Volz, Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London.

Espinosa opened with the core aims of the DRGR Project, a collaboration between the Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP) Center, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London. Its mission is to utilize rigorous, policy-oriented research to advance innovative solutions to address the challenges of 21st century sovereign debt crises.

Volz then provided an overview of the challenging reality facing emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). According to the Group of 20 (G20) Independent Expert Group, EMDEs excluding China will need to mobilize $3 trillion annually, $1 trillion from external sources and $2 trillion domestically, by 2030 to achieve the 2030 United Nations Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement. However, many EMDEs face conditions inhibiting their ability to mobilize investment, including historic levels of external debt, higher interest rates and low growth prospects to 2030.

Volz emphasized the inadequacy of the international community’s approach to managing debt problems over the past three years, pointing to the three shortcomings in the G20 Common Framework. First, middle-income countries do not qualify for treatment under the Common Framework. Second, it does not compel participation from all creditor classes, particularly the private sector and multilateral development banks (MDBs), to engage in debt relief. And third, it relies on incomplete debt sustainability analyses (DSAs) that do not take into account the investment needs of EMDEs to meet the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Paris Agreement commitments.

He then presented key findings of the new report, highlighting the doubling of external Public and Publicly Guaranteed (PPG) debt levels since 2008. What is more, while EMDEs should be mobilizing finance to invest in climate and development, they will pay record amounts to service their external debt in 2024. According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development, 3.3 billion people live in countries that spend more on external debt service than on health or education investments. This is compounded by the fact that accessing private capital markets remains unattainable for most EMDEs.

Volz highlighted that despite the debt-related challenges facing EMDEs, there are inadequate tools to assess which countries need debt relief and how much is needed. Therefore, the new report performs an enhanced DSA that accounts for development and climate change external financing needs following the recommended levels estimated by the G20 Independent Expert Group.

According to this enhanced DSA, in the next five years, an estimated 47 EMDEs would surpass International Monetary Fund (IMF) external debt solvency thresholds as they mobilize capital to meet the 2030 Agenda and Paris Agreement needs. An additional 19 EMDEs lack liquidity and fiscal space for climate and development investment.

Comprehensive Debt Relief for Sustainable Development and Climate Goals

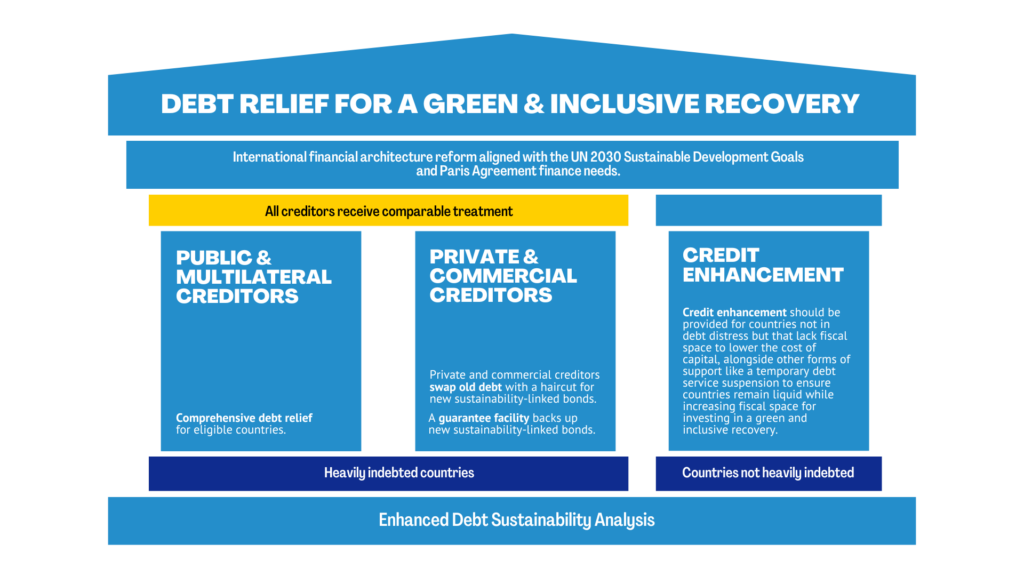

To achieve a fair and efficient debt relief process, the DRGR Project has developed a proposal that is in many ways a modern-day version of the Brady Plan and the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative of the 1990s combined. Jörg Haas presented the three pillars of the proposal, shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Three Pillars of Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery

The first pillar addresses public and multilateral creditors and recommends these creditors provide comprehensive debt relief that not only restores a distressed country to debt sustainability but also puts it on a course to achieve development and climate goals, all while maintaining the financial stability and credit rating of multilateral institutions. Haas emphasized the importance of including the involvement of MDBs, citing findings from another DRGR Project report that estimates their fair share of the burden and explores policy options to preserve their high credit ratings.

The second pillar involves private and commercial creditors granting commensurate debt reductions alongside public creditors with a fair comparability of treatment. To ensure their participation, private creditors would be compelled to enter negotiations through a combination of “carrot” and “stick” incentives.

Finally, under the third pillar, credit enhancement should be provided for countries not in debt distress, but that lack fiscal space to lower the cost of capital, alongside other forms of support like a temporary debt service suspension to ensure countries remain liquid while increasing fiscal space for investing in a green and inclusive recovery.

Volz then went on to present the policy recommendations that emerged from the report. First, Volz underscored the crucial importance of “getting the DSAs right [as] they will determine how the debt problem will be dealt with.” He elaborated that DSAs, which are currently under review at the IMF, need to be enhanced and calibrated to account for critical development and climate investment needs of EMDEs, as well as the potential of climate change and other shocks.

Secondly, the G20 Common Framework must be based on these enhanced DSAs, compel all creditor classes to participate, and deliver a level of debt relief necessary to mobilize financing for climate and development goals.

Finally, credit enhancements and debt service suspension – for example, with a revitalized and enhanced Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) – should be provided to the 19 EMDEs identified as facing liquidity rather than solvency problems and that lack fiscal space for investments in development.

As Volz emphasized, meaningful debt relief is urgently needed to allow at least 47 economically vulnerable EMDEs to maintain debt sustainability while investing in climate and development. Otherwise, the international community risks a potential default on the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement.

Addressing Debt, Climate and Development Challenges: Insights from South Asia, Africa and Beyond

Following the report presentation, Shamshad Akhtar offered insights from Pakistan and the broader South Asian region, shedding light on the intertwined challenges of high debt levels, climate vulnerability, and insufficient investment in sustainable development and climate protection.

Drawing from a recent report by the World Bank, Akhtar highlighted the increase in external debt stock across South Asian countries, with the average standing at 86 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022 compared to 23 percent less than two decades ago.

She emphasized that half of the eight South Asian countries – Afghanistan, the Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka – are in debt distress, undergoing restructuring or at high risk. Akhtar explained that the hesitance among these nations to declare default are due to the complexities involved in debt restructuring.

Pakistan’s utilization of the DSSI was cited by Akhtar as merely temporary relief. She cautioned that the postponement of debt repayment would lead to further complications, diverting resources away from development spending. Akhtar underscored the urgent need for macroeconomic reforms to address these challenges, particularly in a country like Pakistan, which ranks among the top ten most affected by climate change. She concluded by highlighting the significance of initiatives like the DRGR Project in offering comprehensive solutions to these multifaceted issues.

Patrick Njoroge delved into the implementation of the three pillars proposed by the DRGR Project, emphasizing the crucial first step of understanding and communicating the magnitude of the debt problem. He echoed the report’s assertion that urgent action is needed, noting the inadequacy of existing frameworks like the G20 Common Framework in addressing the depth of the crisis. Njoroge emphasized the necessity for swift and ambitious measures to confront these challenges effectively.

Bogolo Kenewendo provided a perspective from Africa, particularly focusing on the continent’s vulnerability to climate change and the lack of finance for climate adaptation. She highlighted the efforts by African leaders to address these issues – such as at the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, the Africa Climate Summit or in the African Union as a new permanent member of the G20 – calling for accompanying regional responses and advocating for reforms in the global financial infrastructure to better serve the needs of African countries. Moreover, Kenewendo underscored the importance of reaching a point where development is not only associated with credit and debt; instead, rapid responses related to climate shocks and resilience should be increasingly enabled by climate and related funds.

During the Q&A session that followed, discussions revolved around the role of special drawing rights (SDRs) and the enhanced DSA in addressing the complexities of austerity, financial stress and the imperative to invest in development and climate resilience. Volz, Akhtar and Njoroge emphasized the need for a broader agenda that includes both debt relief and new finance mechanisms like SDRs. Akhtar reiterated the importance of enhanced DSA in guiding policy decisions, emphasizing the critical need for climate and development sensitivity in the international financial architecture.