A new report from the DRGR project analyzes new data on the level and composition of public and private external sovereign debt for emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs).

By Luma Ramos and Rebecca Ray

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change declared that the world stands at a ‘now or never’ moment. In this decade, nations must make the necessary investments to prevent global warming from surpassing 1.5 degrees Celsius. Without those investments, the world will suffer severe consequences, including devastating human, ecological and economic losses.

Still, an alarming and growing number of emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) have insufficient fiscal space to provide essential services to their citizens and even less to mobilize the necessary resources to meet shared climate and development goals. The macroeconomic scenario of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine, climate shocks and rapid interest rate hikes in advanced economies have depreciated exchange rates and compounded already distressed debt burdens. In 2022, countries began defaulting on their sovereign debt, and more are on the horizon as growth slows and credit conditions worsen. Yet, the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatment has been unable to engage all creditor classes or link debt relief to climate and development.

How can emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) find financial and fiscal stability while making the investments necessary to transition to sustainable and low-carbon economies? How does climate vulnerability impact a country’s debt sustainability? What level of restructuring is required across creditor classes for debt distressed EMDEs to achieve debt sustainability? And how could the G20 Common Framework be reformed to provide debt relief for a green and inclusive recovery?

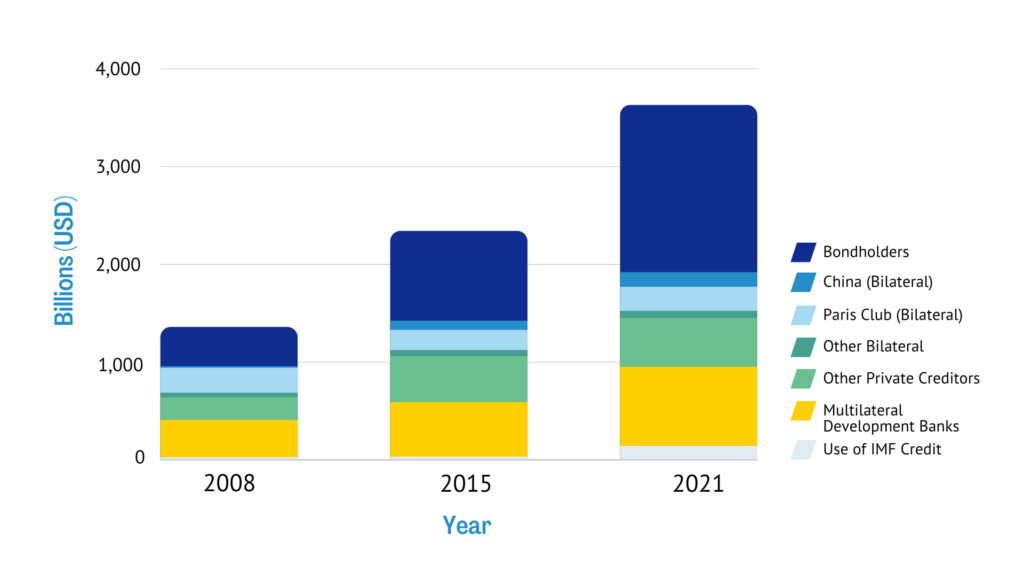

A new report by the Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project reveals EMDEs’ external public and publicly-guaranteed (PPG) debt has more than doubled since the 2008 global financial crisis, jumping from $1.3 trillion in 2008, to $3.6 trillion in 2021.

Climate finance needs make this problem even worse. In Africa, for example, four countries currently have negative fiscal space, or are in need for immediate finance, of over 50 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Once climate finance needs are incorporated, the number of countries with negative fiscal space more than doubles to nine countries.

Figure 1: Developing Countries Debt Composition by Creditor, 2008-2021, in billions

The DRGR Project, a collaboration between the Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP) Center, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London, argues it is time for comprehensive debt reform.

In the report, GDP Center researchers identified 61 countries that are in or near debt distress and need immediate debt relief. These heavily indebted countries, or ‘New Common Framework countries’ (as the report labels them), are among the most climate vulnerable and are likely to have high debt service payments relative to their export income. These countries are allocating a more significant portion of their foreign resources to paying off debt, decreasing their foreign resilience capacity and making their economies highly susceptible to fluctuations in macroeconomic variables.

The proposed solution is a modern-day version of the Brady Plan and the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative of the 1990s. The report articulates a set of positive and negative incentives (“carrots and sticks”) to ensure the participation of the largest number of creditors in the debt restructuring and relief process. It also provides a clear and predictable roadmap of the restructuring dynamics, addressing debtor governments’ hesitation on the costs and benefits of pursuing relief negotiations. The plan ensures that countries get the haircuts necessary to implement their national plans for sustainable development.

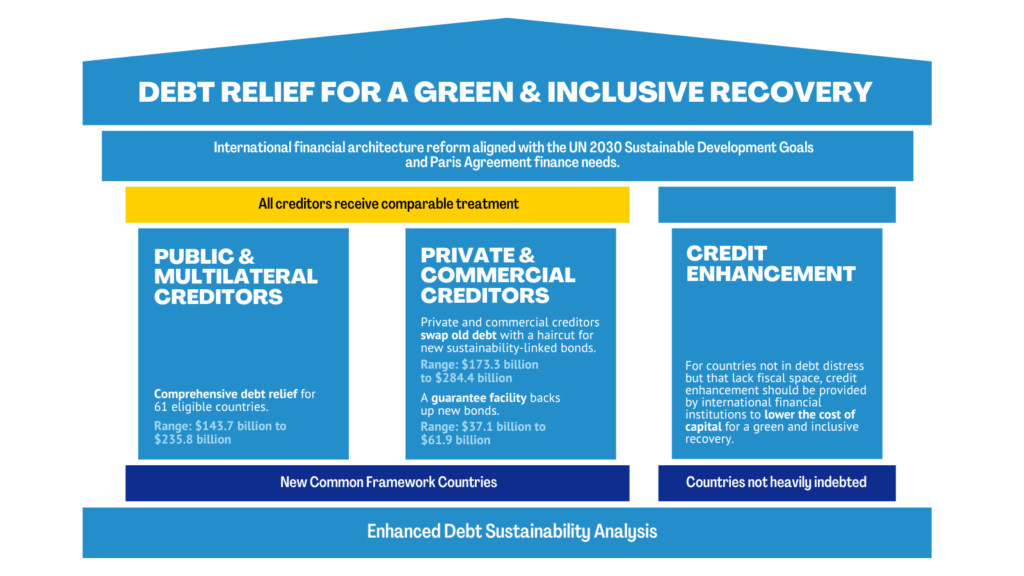

DRGR proposes a three-pillar plan to restructure these New Common Framework countries’ debts, seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Three Pillars of Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery

Note: The ranges of the haircuts mentioned in the figure are in net present value terms.

The first two components focus on debt restructuring for public and private creditors. In the first pillar, debt relief by bilateral creditors and multilateral institutions is provided following historical and HIPC haircuts scenarios (39 percent and 64 percent, respectively). To safeguard multilateral institutions’ creditors preferred status, their losses should be covered by bilateral contributions, the sale of gold or the creation or reallocation of Special Drawing Rights from the International Monetary Fund.

In the second pillar, after a debt haircut, remaining debts are exchanged for newly issued “green and inclusive recovery” or sustainability-linked bonds. Payments are linked to the key performance indicators (KPIs) set out in each country’s Green and Inclusive Recovery Strategy, Climate Prosperity Plan or other such plans as part of the restructuring. These bonds would have better financial terms and creditworthiness as they would be backed by a new guarantee facility administered by the World Bank.

Pillar three includes options for credit enhancements to lower the cost of capital for countries that are not heavily indebted, but are lacking fiscal space to recover from these multiple crises and harness the investments needed to achieve shared climate and development goals. These options include grants, Special Drawing Rights and below market-rate financing.

The report calculates the size of each haircut by creditor class. The estimated level of haircut for Paris Club bilateral creditors, other bilaterals and multilateral institutions under the Historical and HIPC scenarios would be between $143.7 billion and $235.8 billion. Private bondholders and commercial creditors would provide haircuts ranging from $173.3 billion to $284.4 billion. Newly issued sustainability-linked bonds would amount to $160 billion and $271.1 billion, respectively. Finally, the size of the guarantee facility needed to support these new bonds would be between $37.1 billion and $61.9 billion, depending on the level of ambition.

Given the urgency of the matter, as an illustrative example, the authors propose a partial standstill on debt payments of $30 billion for 55 of the 61 heavily indebted countries over the next five years (based on data availability). The suspension may incentivize creditors to participate, accelerate debt restructuring talks and reduce short-term debt payment stress.

The current international financial architecture fails to deliver a sustainable and inclusive path for developing countries, and a broader set of reforms must be in place. The DRGR proposal fills an important part in a reformed framework, proposing a transparent, orderly and comprehensive debt relief scheme to restore debt sustainability and mobilize the necessary resources to meet shared climate and development goals.