How can emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) mobilize the necessary financing to achieve the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement without compromising their debt sustainability or indeed, solvency? A new report by the DRGR Project performs an enhanced global external debt sustainability analysis (DSA) to estimate the extent to which EMDEs can mobilize the recommended levels of external financing without jeopardizing debt sustainability.

By Marina Zucker-Marques

Investing in development and climate while maintaining economic and financial stability is a balance that emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) need to strike in order to meet the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement.

EMDEs (excluding China) need a major investment push to achieve the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement. An Independent Expert Group to the Group of 20 (G20) estimates that EMDEs excluding China will need to mobilize $3 trillion annually, $1 trillion from external sources and $2 trillion domestically, by 2030.

Mobilizing such massive investment volumes will be challenging, especially considering that many EMDEs are currently struggling with high debt burdens and high interest rates that can quickly compound debt vulnerabilities.

How can EMDEs mobilize the necessary financing to achieve the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement without compromising their debt sustainability or indeed, solvency?

A new report by the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project – a collaboration between the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London – performs an enhanced global external debt sustainability analysis (DSA) to estimate the extent to which EMDEs can mobilize the recommended levels of external financing without jeopardizing debt sustainability.

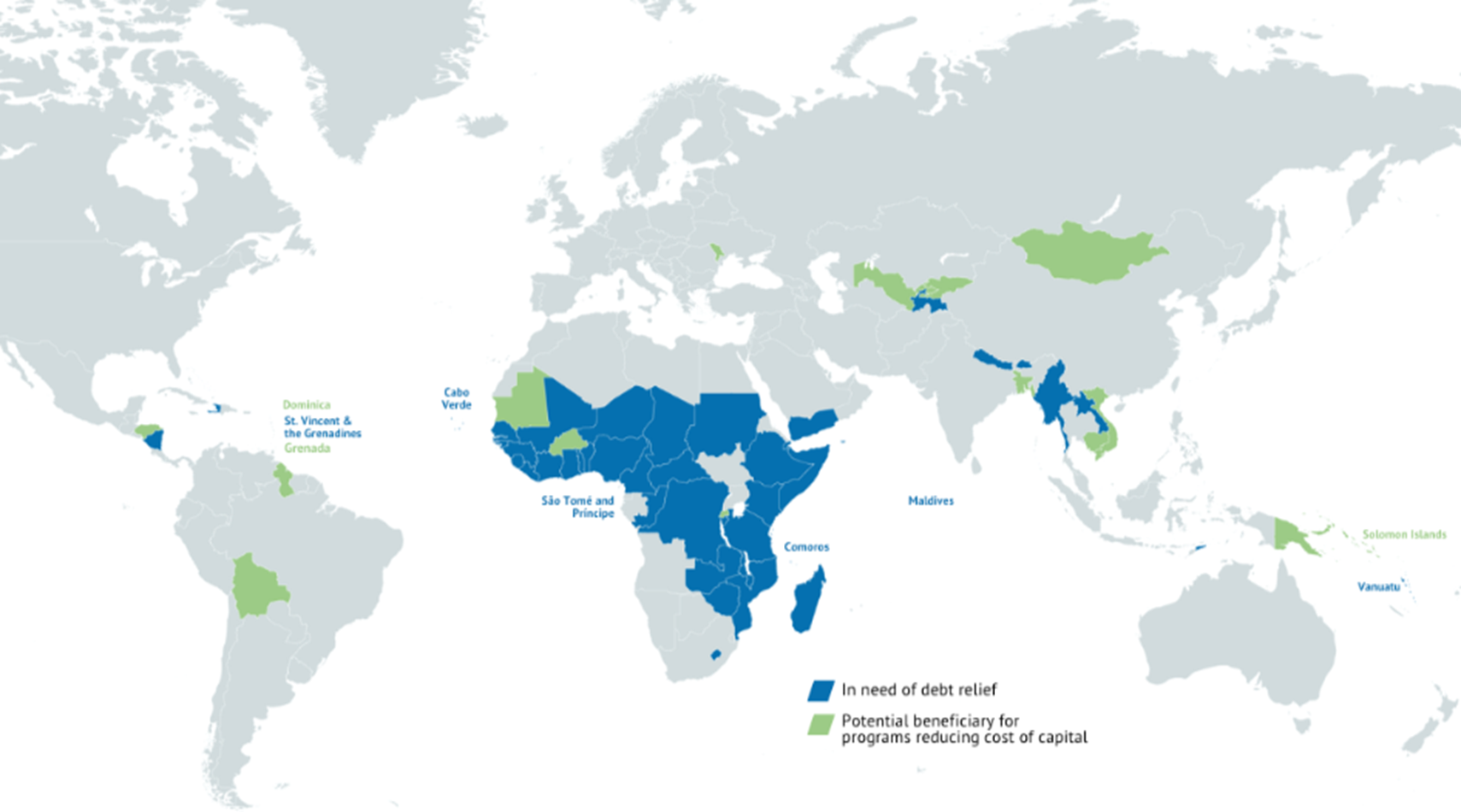

We find that of 66 economically vulnerable EMDEs that are considered low-income countries by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 47 EMDEs with a total population of over 1.11 billion people will face insolvency problems in the next five years as they seek to ramp up investment to meet climate and development goals. An additional 19 EMDEs lack liquidity and fiscal space for climate and development investment and will not be able to finance necessary investments without credit enhancement or liquidity support. These findings indicate that debt relief must be provided if highly vulnerable EMDEs and, indeed, the international community at large, are to have a chance at achieving the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement.

Sky high debt levels during a critical decade

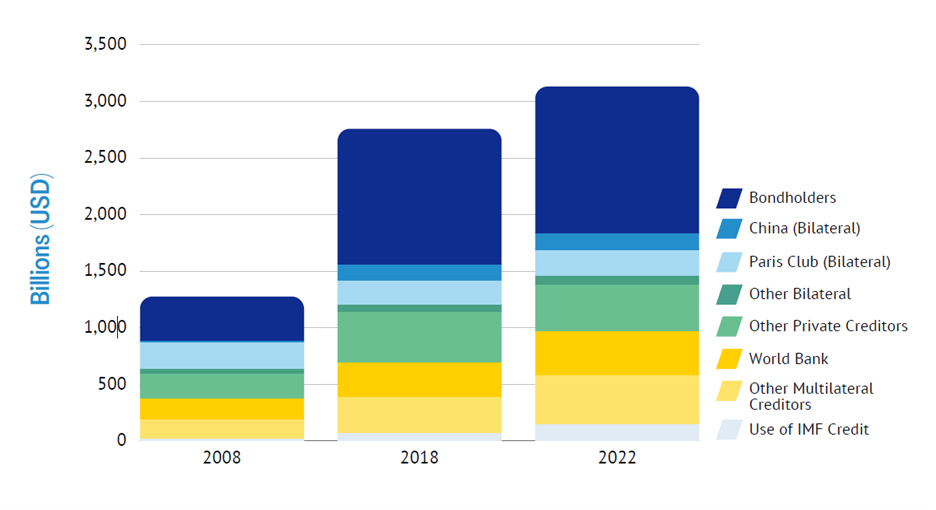

External Public and Publicly Guaranteed (PPG) debt has hit record levels while current debt service is at a height not seen since the 1990s when much of the Global South was on the brink of default. For EMDEs (excluding China), external PPG debt has more than doubled since 2008, reaching $3.1 trillion in 2022, as seen in Figure 1. Moreover, debt service payments are at an all-time high and are crowding out investment in development and climate. While EMDEs should be mobilizing finance to invest in climate and development, they will pay record amounts to service their debt in 2024.

Figure 1: EMDEs’ (excluding China) public external debt composition by creditor, 2008-2022, in USD billions

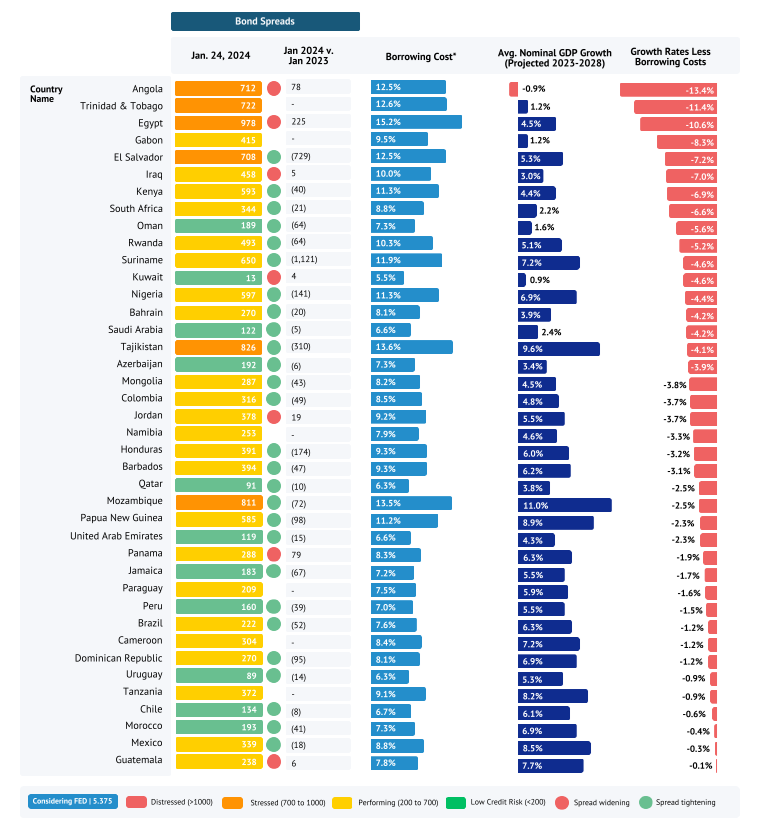

Exacerbating the economic situation, borrowing on private capital markets is out of reach for the majority of EMDEs. Due to bond yields surpassing expected growth rates (see Figure 2 for a selected sample of countries), EMDEs cannot depend on capital markets to refinance or issue fresh debt without endangering their debt sustainability. Although EMDEs do not borrow solely from bond markets and it is important to assess a weighted cost of borrowing, bond markets have become an increasingly important source of finance for EMDEs, pushing up the overall cost of capital. This situation indicates that debt suspension efforts, particularly in high-interest periods, must be carefully implemented to avoid exacerbating debt burdens and are not an effective substitute for debt relief.

Figure 2: Selected countries—Sovereign bond spreads (change between Jan 2023-Jan 2024), borrowing costs and nominal GDP growth projections.

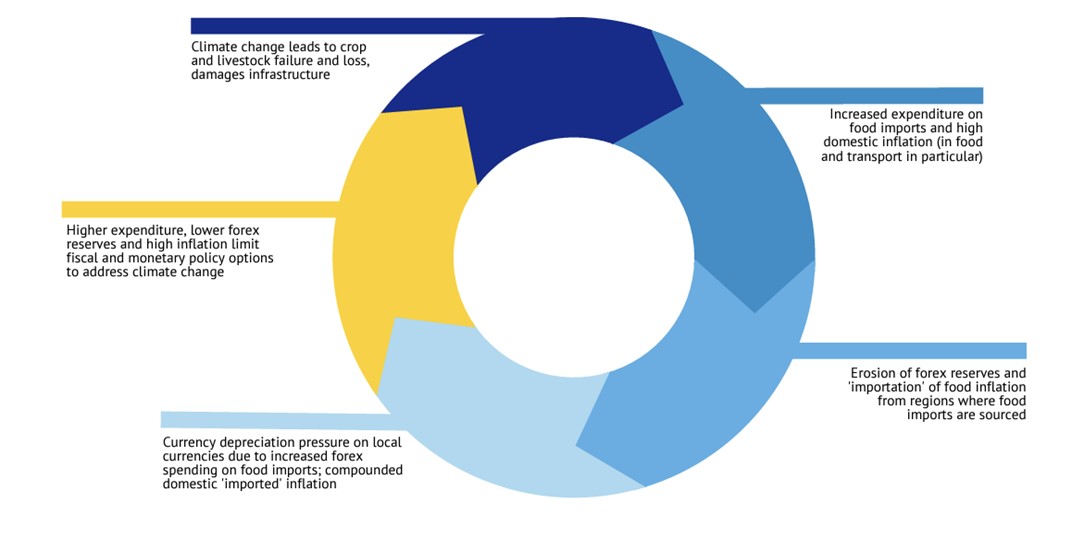

This situation highlights a concerning pattern for EMDEs, where external constraints are aggravated by debt burdens. Apart from macroeconomic shocks – like monetary tightening in advanced economies – EMDEs are also relatively more exposed to climate shocks, such as hurricanes or floods. These physical events devastate critical infrastructure, leading to capital flight, falling exchange rates and soaring costs of borrowing. As Figure 3 demonstrates, this situation can lead to a vicious cycle, where persistent vulnerability to climate change and its associated economic and fiscal shocks hinder the ability of governments to build climate resilience.

Figure 3: The fiscal and monetary policy impacts of climate change

Crafting an enhanced DSA

Despite the debt-related challenges facing EMDEs, the international community lacks adequate tools to assess which countries need debt relief and by how much. The IMF conducts its own DSAs to identify a given member state’s vulnerability to sovereign debt distress and the level of debt relief needed to restore it to debt sustainability. However, the IMF’s DSA has fallen short in several aspects, including biased projections, unrealistic climate investment needs and underestimating the impacts of climate shocks.

The IMF and World Bank Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries (LIC DSF) is currently under reform, creating a crucial opportunity to include realistic assumptions on financing needs for climate and development.

In our enhanced DSA, we accounted for development and climate change external financing needs following the recommended levels estimated by the G20 Independent Expert Group.

The enhanced DSA focuses on 66 of 73 economically vulnerable countries eligible for the LIC DSF, excluding seven countries due to data constraints. The 47 EMDEs identified as being at risk of facing insolvency problems in the next five years for seeking to ramp up investment to meet climate and development goals are depicted in blue in Figure 4. We refer to these 47 EMDEs as the “New Common Framework Countries” (NCF), indicating that they should receive urgent attention under the Group of 20 (G20) Common Framework, the key forum for debt restructuring. A majority of these EMDEs are in Africa, and include economies like Mozambique, Kenya and Cote d’Ivoire, among others.

Additionally, we identified 19 EMDEs that lack liquidity and fiscal space for climate and development investment and will not be able to finance necessary investments without credit enhancement or liquidity support. The 19 EMDEs are depicted in green in Figure 4, and range from economies as diverse as Mongolia, Rwanda and Bangladesh, among others.

Figure 4: External debt sustainability analysis result: Countries in need of debt relief

Sharing the burden of debt relief

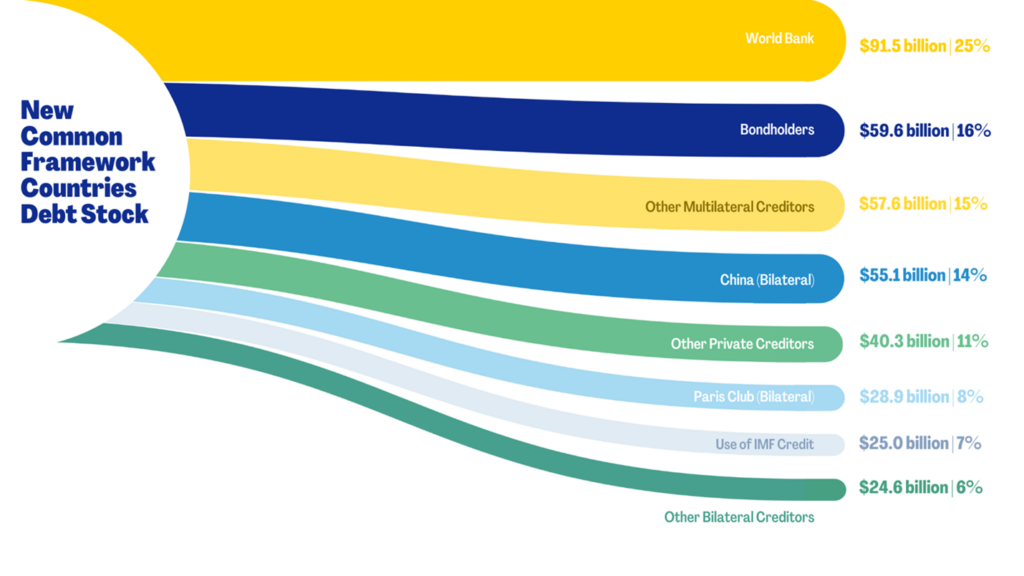

In 2022, the 47 countries identified in the report owed $383 billion in nominal debt (including IMF credits), which, as Figure 5, shows is mostly owed to multilateral creditors ($91.5 billion from the World Bank and $57.6 billion from other multilateral creditors), followed by private creditors ($59.6 billion from bondholders and $40.3 billion from other private creditors), China ($55.1 billion), Paris Club ($28.9 billion), the IMF ($24.9 billion) and other official bilateral creditors ($24.5 billion). This diverse creditor landscape highlights the need for the participation of all creditor classes in debt relief efforts.

Figure 5: NCF (47): Nominal debt stock by creditor groups, 2022, USD billion

However, burden sharing among creditor classes has been a contentious issue and has led to delayed negotiations. For optimum efficiency and effectiveness of sovereign debt restructuring, it is essential to have a clear and transparent approach to equitably sharing the burden among creditors. Building upon previous DRGR Project research, the report suggests the adoption of a “fair” Comparability of Treatment (CoT) rule to account for the distribution of losses depending on the concessional rates of contracted debt. In short, the creditors who charged lower interest rates “ex ante,” like multilateral development banks (MDBs), will be responsible for a smaller proportion of losses, while those that price for the risk of default “ex ante” should bear higher losses in case of a default.

Despite charging for default risks, bondholders have not absorbed proportional loses in cases of debt relief. As recent negotiations with bondholders under the Common Framework—like Suriname and Zambia—show, bondholders’ high remuneration is barely touched even after debt negotiation, while countries in debt distress are left with high debt service obligations that can hamper their economic development. It is fundamental that bondholders adequately participate in debt relief efforts, and for this to happen adequate legislative provisions in key jurisdictions – like New York – should be combined with incentives for bondholder participation in debt relief – like a revisited Brady Bond proposal.

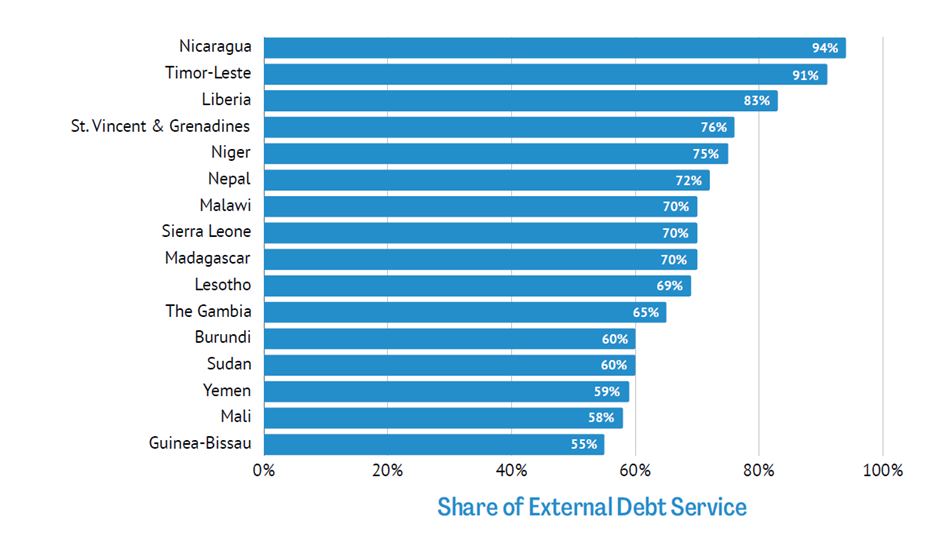

Bondholders are not the only creditor class that need to be more involved in debt relief. Although MDBs often provide high levels of concessionality, for several countries identified as in need of debt relief, achieving debt sustainability hinges upon including MDB claims in debt restructuring negotiations. Figure 6 shows that at least 16 EMDEs that are in need of debt relief will pay over half of their debt service to MDBs over the next five years. It is essential that MDBs participate in debt relief negotiations, albeit in a manner that does not jeopardize their credit ratings.

Figure 6: Average (2023-2030) debt service to multilateral lenders as share of external sovereign debt service.

Debt relief for a green and inclusive recovery

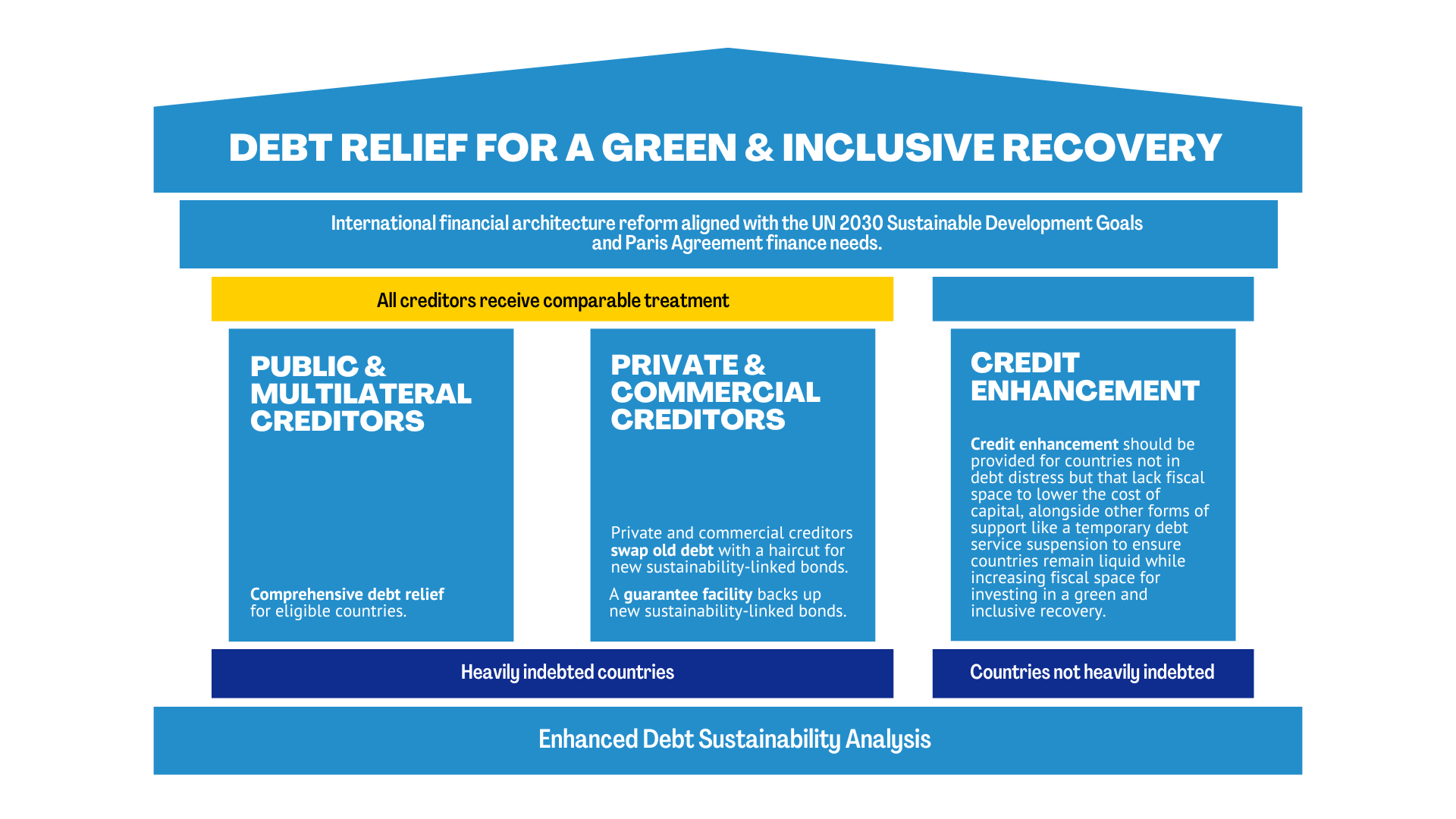

To achieve a fair and efficient debt relief process, the DRGR Project has developed a proposal for concerted and comprehensive debt relief to free resources in heavily indebted EMDEs to foster a just transition to a low-carbon, socially inclusive and resilient economy. The DRGR Project’s proposal rests on three pillars, as seen in Figure 7.

The first pillar states that public and multilateral creditors should grant significant debt reductions that not only return a distressed country back to debt sustainability, but put the country on a path to achieving development and climate goals—in a manner that preserves the financial health and credit rating of multilateral institutions.

Under the second pillar, private and commercial creditors grant commensurate debt reductions alongside public creditors with a “fair” CoT. These creditors must be compelled to enter negotiations through a combination of “carrot” and “stick” incentives.

Finally, under the third pillar, credit enhancement should be provided for countries not in debt distress but that lack fiscal space to lower the cost of capital, alongside other forms of support like a temporary debt service suspension to ensure countries remain liquid while increasing fiscal space for investing in a green and inclusive recovery.

Figure 7: Three pillars for debt relief for a green and inclusive recovery

Policy recommendations

The findings of the report highlight the need for urgent reform in three main areas.

First, DSAs, which are under review at the IMF, need to be enhanced and calibrated to account for critical development and climate investment needs of EMDEs, as well as the potential of climate change and other shocks.

Second, the G20 Common Framework needs to be based on enhanced DSAs, compel all creditor classes to participate and deliver a level of debt relief necessary to mobilize financing for climate and development goals.

Finally, credit enhancements and debt service suspension – for example, with a revitalized and enhanced Debt Service Suspension Initiative – should be provided to the 19 EMDEs identified as facing liquidity rather than solvency problems and that lack fiscal space for investments in development. Here, temporary debt service suspension and reprofiling should be coupled with new financing where the weighted cost of capital is lower than the projected growth rate of participating countries.

The future of EMDEs is at a crossroads. If current economic and policy trajectories persist, the international community will see a default on the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement. Moreover, the repercussions of inaction would result in devastating social, economic and environmental costs that could become irreversible.

However, another pathway exists.

If countries can accelerate investments on climate and development, the world economy can evolve to into one that is low-carbon, more equitable, resilient and conducive to shared prosperity.