Africa is amongst the most climate-exposed regions in the world while also grappling with mounting debt distress. A new policy brief analyzes how debt and climate vulnerabilities reinforce each other and sets out a proposal to link debt relief to climate and development goals, helping African countries escape the debt-climate trap and set the stage for a more sustainable and equitable global financial system.

By Alexander Dryden, Ulrich Volz and Sarah Ribbert

Africa is on the frontlines of two converging crises: mounting debt distress and escalating climate shocks. Public external debt has more than tripled since 2008, with significant increases in the debt owed to private bondholders. The pain of this debt burden has been worsened by increases in global borrowing costs and a continued decline in African currencies versus the U.S. dollar.

In our new policy brief published by the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project, Alex Dryden and Ulrich Volz show how Africa’s debt burden and climate vulnerability are reinforcing one another. Many of the continent’s economies are among the most climate-exposed in the world, yet the region has received only a fraction of the finance it needs for adaptation. Shockingly, Sub-Saharan Africa now spends more on external debt service than it receives in climate finance. To break this cycle, we call for debt treatment to be explicitly linked to climate and development goals, alongside reforms to the IMF’s debt sustainability analysis and expanded liquidity support.

Debt Has Tripled, But Fiscal Space Has Collapsed

Over the past 15 years, Africa’s external debt has more than tripled, climbing from roughly US$200 billion in 2008 to over US$700 billion in 2023. Much of this surge is driven by borrowing from private bondholders, whose share of debt ballooned from US$25 billion to nearly US$186 billion.

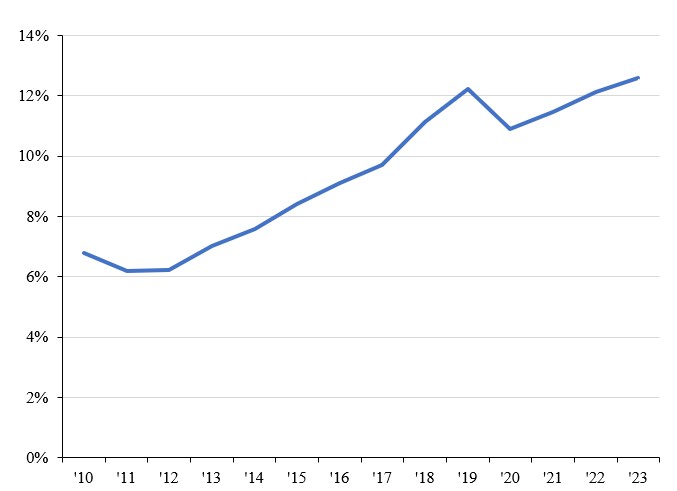

At the same time, African currencies have depreciated sharply against the U.S. dollar, while global borrowing costs have surged. Together, these dynamics mean African governments now spend unprecedented amounts and servicing their debt. Figure 1 shows that between 2012 and 2023, the average share of government expenditure devoted to interest payments doubled, rising to 12.7 percent in 2023. More than half of African countries now spend more on debt service than on health care.

Figure 1: African Government Interest Payments (Percentage of Government Expenses)

Climate Needs Far Outstrip Available Finance

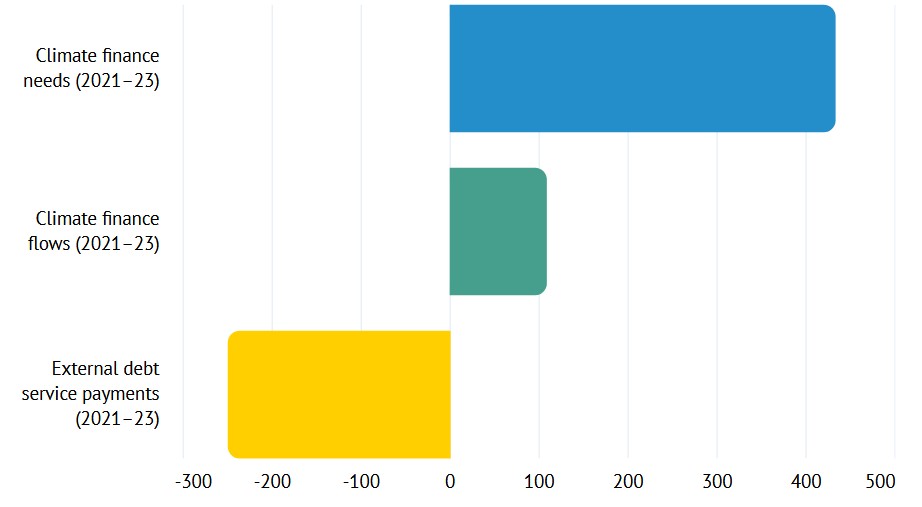

This fiscal squeeze collides with Africa’s colossal climate investment needs. Sub-Saharan Africa will require more than US$1.4 trillion this decade – about US$143 billion annually – to meet adaptation and resilience goals. Yet actual climate finance flows from 2021 to 2023 average just US$35 billion per year (Figure 2). Worse still, more than half of this comes in the form of new debt rather than grants, further fueling unsustainable borrowing.

In effect, countries are borrowing to protect themselves against the very climate shocks that worsen their debt burdens. Meanwhile, African governments are projected to spend US$865 billion on debt servicing over the same decade – nearly as much as they need for climate resilience.

Figure 2: Sub-Saharan Africa: Climate Finance Needs, Flows and External Debt Service Payments (cumulative figures in US$ billions)

The IMF Is Underestimating the Risks

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) is the global benchmark for assessing sovereign debt risks. Yet its framework fails to account for the costs of climate resilience and sustainable development. As a result, many African economies appear “sustainable” on paper – until crises erupt.

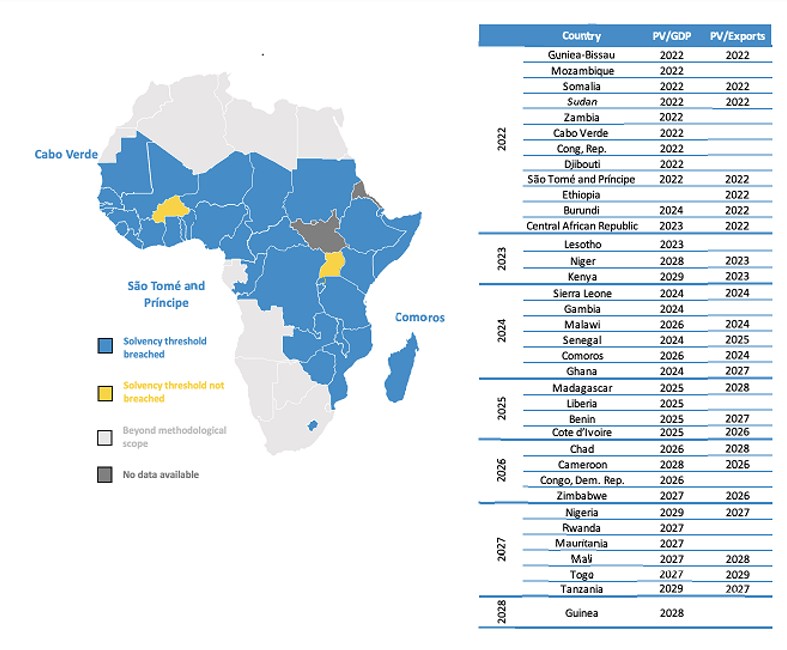

An enhanced DSA methodology (building on the IMF’s Low-Income Country Debt Sustainability Framework) that incorporates climate and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) spending paints a starkly different picture. Our analysis last year was already gloomy, but the situation has deteriorated further. Our updated analysis in Figure 3 shows that by 2023, 15 African economies had already breached solvency thresholds. By 2029, all but Burkina Faso and Uganda are projected to exceed them if necessary climate and development investments are included.

Figure 3: External Debt sustainability Analysis Results Under Baseline Scenario: Countries Breaching Solvency Thresholds by Year

Recent Political Momentum on Debt is Unprecedented

At the same time, debt has risen quickly on the political agenda. In 2024, the African Union adopted the Lomé Declaration, its first joint position on debt reform. Momentum carried into 2025 at the UN’s Fourth Financing for Development Conference in Seville, where African negotiators pushed for a UN Framework Convention on Sovereign Debt. South Africa has also put debt sustainability at the centre of its G20 Presidency, convening an African Expert Panel on Debt. Other initiatives such as the Jubilee Commission, the UN Secretary-General’s Expert Group on Debt and the African Leaders Debt Relief Initiative, have amplified calls for reform. Yet, despite this growing awareness, concrete action and systemic reform remain elusive.

The DRGR Proposal: Linking Debt Relief to Climate Resilience

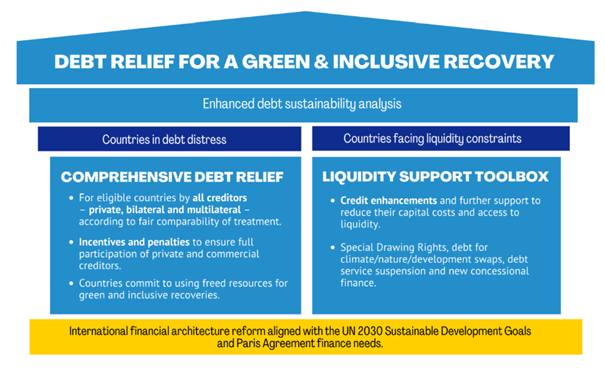

To address the debt and climate crises, the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project calls for a bold restructuring of how debt is assessed and managed. Its proposal is built on three components (Figure 4):

- Reform the DSA framework so that debt sustainability assessments fully incorporate climate and development investment needs.

- For economies in distress, meaningful debt relief has to be provided across all creditor classes, including private and multilateral lenders, combined with fresh concessional finance.

- Countries facing liquidity constraints should be supported through credit enhancements, SDR reallocations, concessional lending, and innovative instruments such as debt-for-climate swaps.

Countries benefitting from debt relief should commit to directing freed resources into green and inclusive development strategies, aligned with Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and SDG implementation plans. Transparency, enhanced debt standards, and strengthened public financial management would form part of these commitments.

Figure 4: Two Pillars for Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery

Turning Momentum into Action

The political momentum on debt reform is undeniable – but without systemic change, Africa risks being locked into a cycle of debt, vulnerability, and underdevelopment. The upcoming G20 Summit is a chance to turn recognition into action.

Leaders should expand the Common Framework to include middle-income countries, ensure all creditors participate fairly, and integrate climate and development spending into the IMF’s debt assessments. Automatic debt standstills in times of crisis, a global debt registry for greater transparency, and stronger liquidity support – including SDR reallocations and debt-for-climate swaps – are essential next steps. Crucially, any debt relief must be tied to green and inclusive recovery strategies so that fiscal space is directed toward resilience, decarbonisation, and the SDGs.

By taking these steps, the G20 can help African countries escape the debt-climate trap and set the stage for a more sustainable and equitable global financial system.