Latin America and the Caribbean stand at the crossroads of unsustainable debt burdens, worsening climate shocks, and stalled development goals. A new policy brief sets out how tackling looming sovereign debt problems could restore fiscal space for climate action and development. It highlights innovative instruments such as debt-for-nature swaps and disaster clauses, while calling for urgent reforms to the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Analyses and the wider global financial framework.

Alex Dryden, Maria Fernanda Espinosa and Ulrich Volz

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) stand at the crossroads of three converging crises: unsustainable debt burdens, worsening climate shocks, and stalled progress toward development goals. Together, these pressures are eroding fiscal space, draining public resources, and leaving the region more exposed to future disasters.

In a new policy brief from the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project, we set out how tackling looming sovereign debt problems could help Latin American and Caribbean countries regain the fiscal space needed to confront the climate emergency and advance their development goals. The brief also highlights the role of innovative instruments, such as debt-for-nature swaps and disaster clauses, that can ease pressure on public finances while supporting resilience. At the same time, it calls for urgent reforms to the International Monetary Fund’s Debt Sustainability Analyses (DSA) and to the wider global financial framework so that they fully account for climate risks and channel investment into resilience-building and sustainable growth.

A Debt Burden That Crowds Out Development

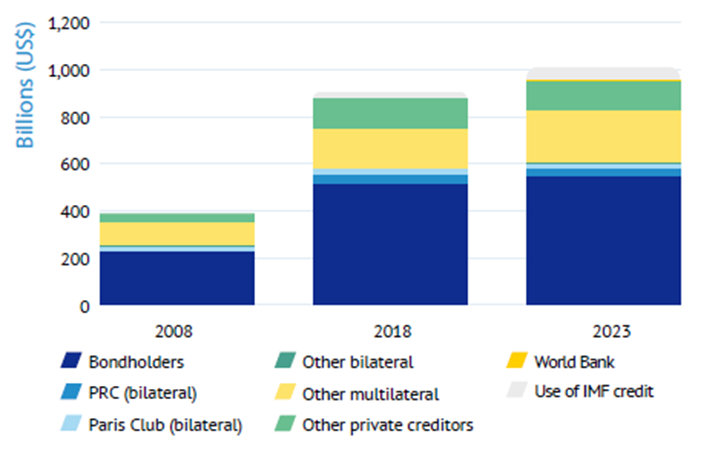

Across the region, public external debt has now surpassed US$1 trillion, with average gross debt hovering around 70 per cent of GDP, up from just 45 per cent in 2008. As shown in Figure 1, the scale of the increase is striking: over the past 15 years, external debt levels throughout LAC have risen by 158 per cent. In the Caribbean alone, the stock of external debt has risen 170 per cent from US$20 billion in 2008 to US$54 billion in 2023. Central America and South America saw similarly sharp increases of 143 per cent and 169 per cent respectively over the same period. For some small island developing states (SIDS) debt ratios now exceed 100 per cent, leaving them acutely vulnerable when disaster strikes.

Figure 1: The public external debt composition (in US$ billions) by creditor type for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2008–2023

Rising global interest rates have compounded these pressures, pushing average sovereign bond yields up by more than 450 basis points since 2019 (see Figure 2). At the same time, prolonged currency depreciations, which have been particularly acute in countries such as Suriname, Brazil, Mexico, and Jamaica, have made servicing foreign-denominated obligations far more costly.

Figure 2: Average yield of Latin American US$ Government Bond Index*

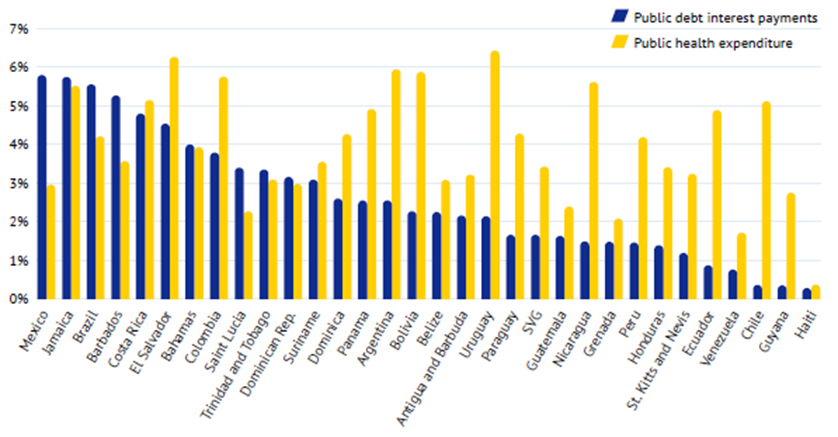

In practical terms, governments are diverting ever larger shares of their budgets to creditors rather than citizens. As shown in Figure 3, between 2021 and 2023, eight countries, including Mexico, Jamaica, Barbados, and Brazil, spent more on interest payments than on public health.

Figure 3: Health expenditure and interest repayments in LAC as a percentage of GDP (annual average for 2021-2023)

Fiscal suffocation makes it nearly impossible for governments to invest in climate resilience, infrastructure, or poverty reduction. Schools and hospitals are under pressure, while disaster preparedness is often postponed until it is too late. Progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals has slowed dramatically: more than half of economies in LAC are stagnating — or even regressing — on targets such as reducing inequality, ensuring food security, and building strong institutions. Instead of moving toward a sustainable future, many countries find themselves trapped in a cycle of sacrifice, forced to choose between servicing debt and protecting their people.

Climate Disasters Turn Debt into a Trap

The climate dimension makes this debt overhang far more dangerous. LAC is the world’s second most disaster-prone region, behind only sub-Saharan Africa. Hurricanes, droughts, floods, and earthquakes have already cost the region over US$110 billion since 2000. In Dominica, Hurricane Maria caused damages equal to 269 per cent of GDP in 2017; Grenada lost 165 per cent of GDP to Hurricane Ivan in September 2004, pushing the country into a state of default the following month.

Each shock forces governments to borrow more for reconstruction, compounding already unsustainable debt. The result is the vicious cycle where disasters fuel debt, which in turn crowds out investment in resilience. This underinvestment then magnifies the costs of the next disaster. Despite contributing less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions, Caribbean SIDS are among the hardest hit by this vicious pattern of recovery followed by reversal.

Innovations Show Promise, But Aren’t Enough

The region has pioneered creative solutions. Belize’s 2021 “blue bond” debt-for-nature swap cut its debt by 12 per cent of GDP while financing long-term marine conservation. Barbados, Ecuador, and the Bahamas have since followed with their own swap deals, some of them on a far larger scale than ever attempted before. These transactions show how debt restructuring can be tied directly to climate and environmental commitments, creating a model that is drawing international attention.

Grenada and Barbados have also broken new ground by issuing bonds with “disaster clauses” that allow repayment suspensions after major shocks — Grenada became the first country to invoke such aclause in 2024 after Hurricane Beryl, immediately freeing up over US$12 million in fiscal space for emergency relief and rebuilding. Meanwhile, Barbados’ 2025 debt issue was particularly noteworthy because it included a pause clause in the bond contract without investors without charging a premium by investors. These experiments prove that financial innovation is possible even in small and vulnerable economies.

Yet while they point in the right direction, they are not silver bullets. Debt-for-nature swaps often come with high administrative costs and complex legal structures, while questions linger over the sovereignty implications of placing conservation funds under external oversight. Disaster clauses, meanwhile, remain rare and relatively untested outside the Caribbean. Without systemic reform of the broader financial architecture, these instruments can ease pressure only at the margins. The challenge is to build on these breakthroughs and scale them into a framework that provides consistent, predictable relief across the region.

Toward a New Debt and Climate Architecture

What the region needs is a framework that links debt relief directly to climate action and inclusive development. This framework should rest on two complementary pillars:

- For distressed economies: deep and comprehensive restructuring with participation of all creditors, bilateral, multilateral, and private, under enforceable comparability of treatment. Relief must be paired with concessional finance to invest in resilience, green infrastructure, and social protection, ensuring that debt reduction translates into tangible progress for people and the planet.

- For solvent but liquidity-constrained economies: expanded concessional lending from multilateral development banks, targeted reallocation of Special Drawing Rights, and wider adoption of climate-responsive debt instruments such as swaps, green bonds, and disaster clauses. These measures can lower borrowing costs and create fiscal breathing space without forcing countries into crisis before action is taken.

Crucially, these reforms must be embedded in a global debt and climate finance architecture that provides predictable liquidity, affordable development finance, and a credible sovereign debt workout process, moving beyond ad hoc fixes to deliver a durable solution for the region.

The Cost of Inaction

Unless policymakers confront this reality, the region risks another lost decade defined by repeated crises, strangled fiscal space, and deepening inequalities. Technical fixes alone will not be enough – political leadership is urgently required to drive systemic reform. The upcoming IMF/World Bank Annual Meetings in October provide a chance to set the tone by acknowledging that Latin America and the Caribbean face a debt crisis, and that failing to act will only deepen instability. The EU–CELAC summit in November offers a further platform for concrete commitments.

Here, Europe has a particularly important role to play. Climate finance and green investments will achieve little in debt-strapped economies unless they are tied to systemic reform. LAC does not need incremental pledges— it needs Europe‘s political and financial backing for genuine systemic reform. This includes advancing a climate-smart Debt Sustainability Framework, swiftly operationalizing the SIDS Debt Sustainability Support Service, and improving the G20 Common Framework to deliver faster processes, full creditor participation, and enforceable comparability of treatment. Enhancing dialogue and fostering joint action between the EU and LAC on debt and climate finance could be an important step toward more effective global financial governance.

With bold changes, LAC can break the cycle — building fiscal resilience, accelerating climate adaptation, and realigning debt management with sustainable development. Without them, the region will remain trapped in a pattern of crisis and recovery, bearing the costs of a system that continues to overlook its most urgent needs.