Find answers to frequently asked questions on the debt crisis, the DRGR proposal and how to guarantee sustainable development.

by Rishikesh Ram Bhandary and Marina Zucker-Marques

In the Global South, a silent sovereign debt crisis is unfolding. In many low- and middle-income countries, debt service is impeding crisis responses, worsening development prospects and compromising the ability to adapt to the impending climate crisis, as well as threatening the achievement of the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project is a collaboration between the Boston University Global Development Center, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Centre for Sustainable Finance, SOAS University of London to advance innovative solutions to address the challenges of the 21st century sovereign debt crises.

Why is debt relief needed now?

While debt levels were already on the rise in the lead up to the COVID-19 pandemic, the converging crises of the pandemic, supply chain shocks, high interest rates, soaring food and energy prices and sluggish economic growth means that many countries are having trouble servicing their debt payments. Building on analyses by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the DRGR Project estimates that 69 countries need immediate debt relief. With countries directing a large fraction of their tax revenue to debt service payments, many are underinvesting in areas critical for health and development. With debt relief and a clean balance sheet, countries will be able to unlock much needed investment for development and green adaptation.

How is climate action related to debt distress?

The urgency of addressing climate change means that countries must mobilize resources to shift their economies towards low-carbon, climate resilient trajectories in a rapid but orderly way. Many countries do not have the fiscal space to make the investments needed to foster climate resilience. In a 2022 working paper, the IMF found that only seven of 29 low-income countries had the fiscal space needed to make climate investments. Furthermore, many climate-vulnerable countries are facing increasingly high costs of capital, which further amplifies debt distress by increasing debt service payments and deterring critical investments.

What is the international community doing about debt distress?

The Group of 20 (G20) set up a Common Framework for Debt Treatment. The Common Framework is designed to help countries restructure their debt and restore macroeconomic stability. The Common Framework builds on the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which was created to provide temporary and partial standstill on external debt payments from the poorest countries.

There are three shortcomings of the Common Framework. First, it is not equipped with the tools and instruments to compel the participation of all creditor classes, in particular, private creditors. Second, the Common Framework has yet to deliver meaningful debt relief in a timely manner. Finally, it does not actively reflect the development and climate change investment needs of countries in the debt re-negotiation and resolution process.

What is the DRGR Project proposal?

The DRGR proposal is a holistic approach to swiftly address sovereign debt problems and scale up and sustain investment in climate resilience and sustainable development. While the G20 Common Framework has been a step in the right direction, it has yet to deliver meaningful debt relief. The DRGR proposal offers a set of incentives and sticks to ensure that the widest possible section of creditors participate in the restructuring and relief process. Furthermore, it also addresses the hesitation that many debtor governments have in seeking restructuring by providing a clear and predictable roadmap of the steps involved and ensuring haircuts are sufficient for countries to meaningfully invest in their national plans on sustainable development.

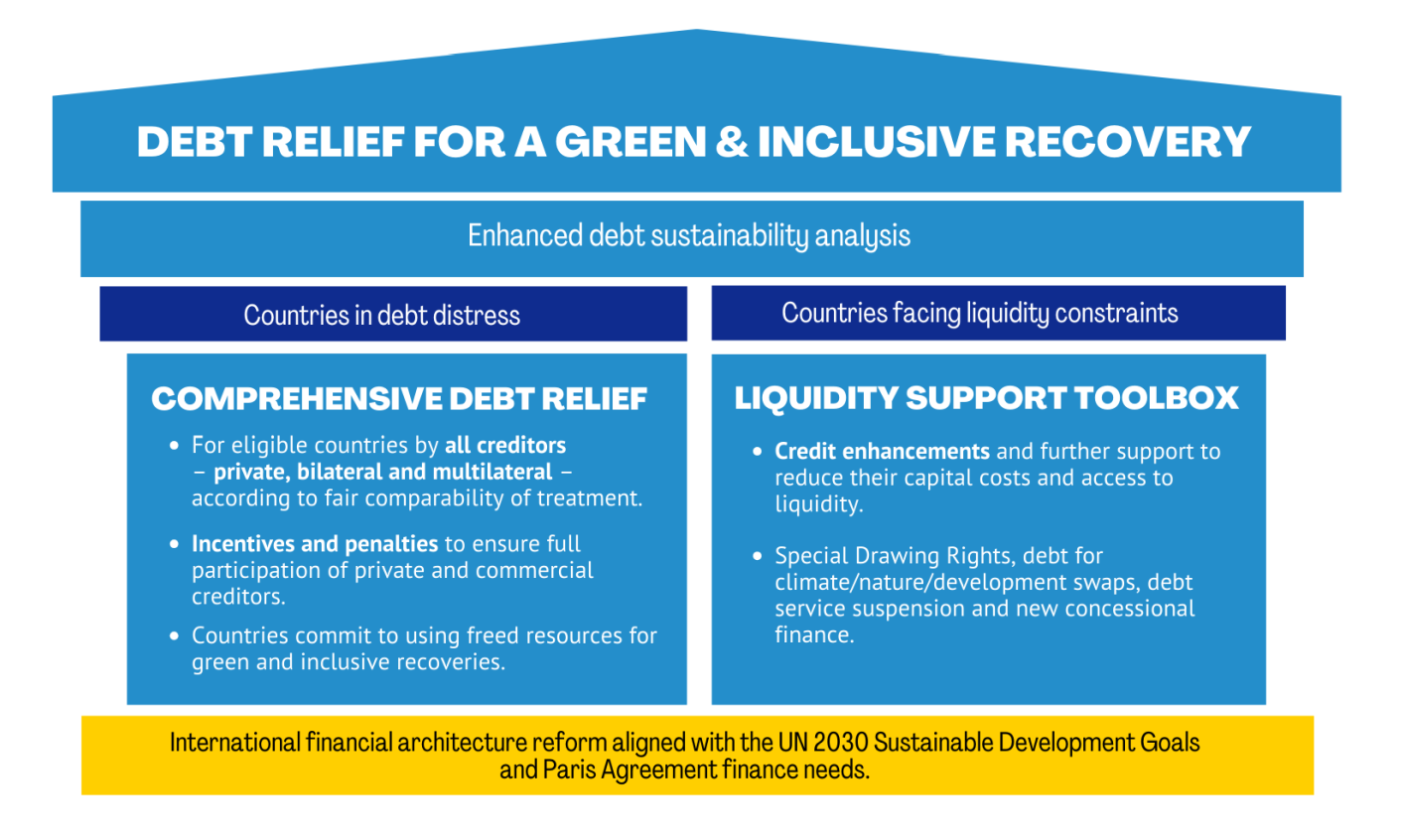

The DRGR proposal requires three elements:

- Comprehensive and speedy reform of debt sustainability analysis (DSA): An enhanced Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) framework is urgently needed to incorporate climate risks and critical investment needs for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and climate targets. Current DSAs prioritize a country’s ability to service debt but overlook the need for investment in climate resilience and just transitions. By integrating climate considerations, the international community can align debt relief with sustainability goals and better differentiate between countries requiring debt relief and those needing liquidity support.

- For the group of countries in need of debt restructuring and relief, meaningful debt relief needs to be provided. The participation of all creditor classes, including private bondholders and MDBs, in debt restructuring is critical. Fair comparability of treatment rules to determine haircuts are needed to ensure equitable burden-sharing. Incentives and penalties are required to safeguard private and commercial creditors’ full participation in debt restructuring. Debt relief needs to be coupled with fresh financing at concessional rates to enable sustainable recoveries. Countries receiving debt relief need to commit to using freed-up fiscal resources to invest in green and inclusive recoveries in line with their Nationally Determined Contributions and national implementation plans for the SDGs. Countries receiving debt relief also need to subscribe to establishing full public debt transparency and enhancing public debt standards.

- Non-distressed countries facing liquidity constraints should be provided with credit enhancements and further support to reduce their capital costs and access to liquidity. Besides the issuance of new Special Drawing Rights (SDR) and the rechannelling of SDRs from advanced countries, efforts need to be reinforced to provide new concessional finance by MDBs. Instruments like debt for climate/nature/development swaps and credit enhancements for new sovereign sustainability linked bonds can complement this.

This approach comprises two pillars: Based on the performance of an enhanced DSA, countries would be classified as either facing debt distress or liquidity constraints, each requiring distinct treatment.

Figure 1: Two Pillars of the DRGR Proposal

Resources that are freed up either by debt relief measures or by credit enhancements will be channeled to support recoveries in a sustainable way, boosts economies’ resilience and foster a just transition to a low-carbon economy. Countries’ specific investment priorities should be informed by their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (as determined through the Paris Climate Agreement), their “Climate Prosperity Plans” or another document that outlines spending target.

How does the proposal ensure the involvement of private creditors?

The proposal advances a series of carrots and sticks to encourage private creditor participation. A debt payment standstill will act as a ‘stick’ encouraging early participation and speedy resolution. The guarantee facility will allow old debt – the existing stock of debt prior to the restructuring effort – to be swapped out for new bonds that are backed by the facility. These new bonds with high credit ratings will be a major carrot. Other sticks include lending into arrears and legislative fixes to compel creditor participation. Applying the IMF’s policy of lending into arrears can give creditor countries that are in default with other creditors significant bargaining leverage.

Does linking development and climate goals to debt relief effectively amount to ‘green’ conditionally on debtor countries?

The DRGR proposal does not impose conditionalities on debtor countries of any kind, green or otherwise. Country ownership of the spending targets is one of the key principles of the proposal.

Countries will use freed up resources to support nationally determined green and inclusive recovery plans. A core tenet of the DRGR proposal is that these plans must have country ownership. Many countries have already articulated their commitments related to green and inclusive recovery. For example, all countries that are parties to the Paris Agreement have NDCs. The bonds that will be issued in exchange of old bonds following a haircut will have key performance indicators that are directly linked to the implementation of these country-owned plans.

What assurances are there that the debt relief would be channeled to supporting a green and inclusive recovery?

Country-owned development and climate change plans are the cornerstone of the DRGR proposal. These plans form the basis for broader negotiations. Furthermore, performance linked bonds that are directly rooted in country-owned plans will also help to draw a direct link between debt relief efforts and national green and inclusive recovery efforts.

Given the severity of the climate crisis, is debt relief really the most effective solution in terms of financing mitigation and adaptation? Would it make more sense to put the money in dedicated funding initiatives (like the Green Climate Fund (GCF) or the Loss and Damage Fund)?

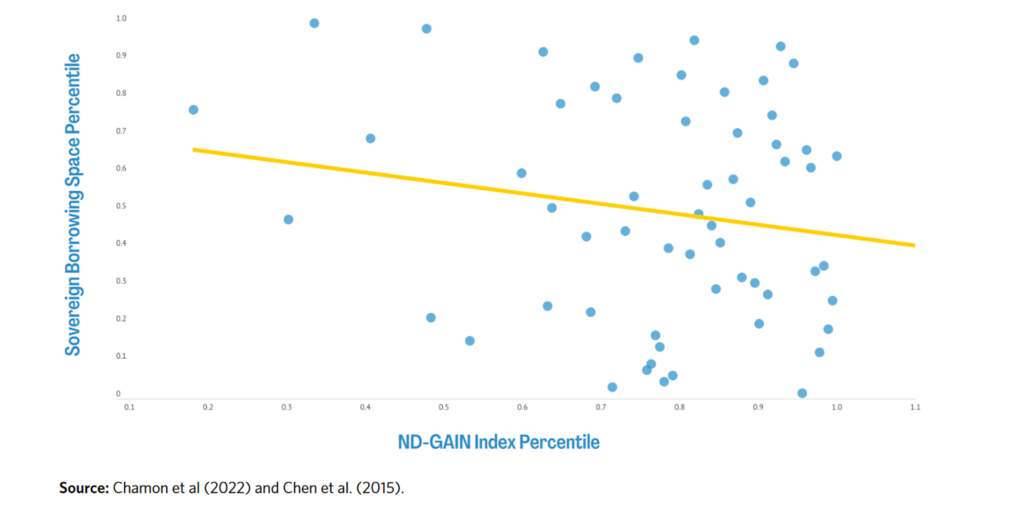

Our analysis shows that many of the countries with lower sovereign borrowing space are also climate vulnerable and necessitates greater adaptation investment, as shown in Figure 2. These countries require debt relief so that they create the fiscal space to invest in mitigation and adaptation activities. Moreover, debt relief is one element of a broader set of efforts required to facilitate a low-carbon, resilient development pathway. More resources in the form of grants for dedicated funding initiatives, like the GCF, will have to be a part of this larger effort as well.

Figure 2: Climate Vulnerability and Sovereign Borrowing Space

How could multilateral development banks (MDBs) participate in debt relief efforts without harming their preferred creditor status and AAA rating?

For several debt and climate vulnerable countries, external debt is owed mostly to MDBs, making their involvement in debt relief fundamental. A new report by the DRGR Project recognizes the crucial role MDBs play in providing affordable financing for developing countries and presents policy alternatives to preserve the AAA rating of MDBs. Based on historical experience with MDB involvement in debt restructuring, multilateral institutions could be backed up by a combination of bilateral contributions and internal resources (e.g., a portion of their operational results). Additionally, donors and MDBs could explore innovative alternatives. Among them, an International Financial Transaction Tax could fund MDBs’ debt relief by targeting various financial transactions. Alternatively, by increasing the equity of MDBs, it would be possible to free a fraction of precautionary balances to be used for debt relief efforts. Finally, the DRGR Project supports an intra-creditor fair burden sharing of losses, meaning that because MDBs provide highly concessional lending terms, they should bear relatively less losses than other creditors with higher interest rates.

Is it possible to restore debt sustainability without addressing domestic debt?

A composite picture of a country’s fiscal sustainability considers its external and internal obligations. However, given the macroeconomic headwinds faced by countries, especially in terms of exchange rate fluctuations and lack for foreign currency liquidity, servicing foreign currency denominated debt has become a major concern for many countries. Moreover, domestic debt restructuring must be carefully considered given the possible negative effects it can generate on domestic financial stability. Therefore, the restructuring of external debt should be the priority in a debt relief effort, as it would bring the highest efficiency in terms of economic recovery without jeopardizing economic stability.