In the midst of a complex web of crises, Malawi is facing a debt restructuring process that does not address the depth of its challenges. To embark on a path to sustainable development and economic recovery, countries like Malawi need a holistic approach that takes into account all aspects of their economic and social realities – and includes all creditor classes.

by Marina Zucker-Marques

Amid a multitude of emergencies – natural disasters, acute food insecurity and high levels of poverty – Malawi recently borrowed from an International Monetary Fund (IMF) program, and is currently undergoing debt restructuring.

Malawi urgently needs additional financing and freed fiscal space to respond to these emergencies and to invest in resilient and low-carbon development.

However, the present debt restructuring negotiations cover just one-third of Malawi’s external debt, rendering it unlikely to produce a meaningful change in Malawi’s fiscal space.

The other two-thirds of Malawi’s debt is owed to multilateral development banks (MDBs), which are considered “super-senior creditors,” and hence are precluded from debt relief efforts. This limitation not only hinders effective debt restructuring but also disrupts Malawi’s path towards economic stability and sustainable development.

Malawi is not a unique case, as more than 20 other developing countries with MDBs as their main creditor share similar constraints in debt restructuring. Despite the Group of 20 (G20) explicitly calling for MDBs to develop options to share the burden of debt relief efforts, they have as yet not agreed to contribute to debt relief efforts under the G20’s Common Framework. As of the time of writing, Malawi has not applied to the Common Framework, an indication that excluding MDBs from debt relief efforts under the Common Framework effectively reduces the pool of eligible countries that can seek debt treatment.

This month’s 2023 United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP28) has emphasized the need for developing countries to boost investments in climate and development. Achieving the levels of finance necessary will necessitate a combination of debt relief, alongside a substantial increase in aid, grants and affordable finance from MDBs and official creditors alike.

At such a critical moment, including all creditor classes in debt restructuring is essential to provide meaningful relief and to increase fiscal space.

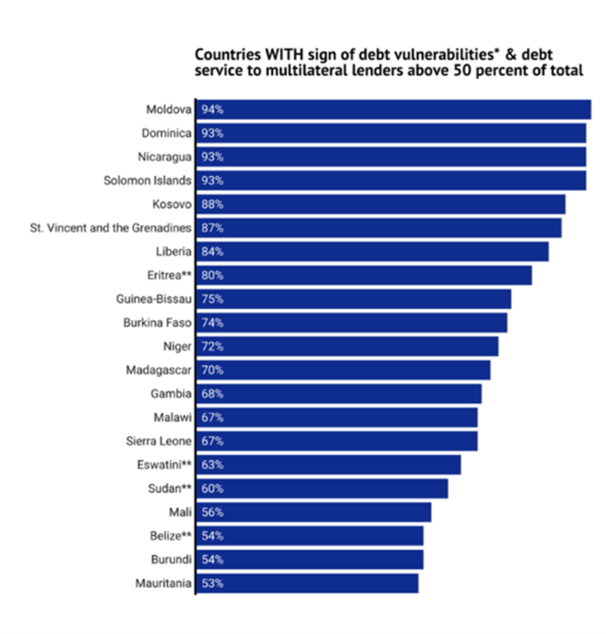

Multilateral development banks in debt restructuring

In a recent study, we highlighted the importance of including MDBs in debt relief and how it can be safely implemented without jeopardizing the MDB business model and credit ratings. For 27 countries exhibiting signs of debt vulnerabilities, most of their external Public and Publicly Guaranteed (PPG) debt is owed to multilateral lenders. Despite the lower interest rates typically offered by MDBs, 21 countries with signs of debt distress will pay over half of their external sovereign debt service to MDBs from 2023-2029, as shown in Figure 1. In other words, only with the participation of MDBs in debt relief negotiations can these countries restore macroeconomic stability and move towards a path of sustainable development.

Figure 1: Average (2023-2029) Debt Service to Multilateral Lenders as Share of External Sovereign Debt, by Country Group

Malawi is a case in point of the importance of MDB participation in debt relief. In November 2023, the IMF approved a 48-month arrangement under the Extended Credit Facility (ECF) for Malawi, amounting to $175 billion, or 95 percent of their IMF quota, which determines the maximum IMF loan amount a member can obtain. According to the IMF’s First Deputy Managing Director, Gita Gopinath, relying only on fiscal adjustments and IMF financing would not be sufficient to deliver macroeconomic stability, making external debt restructuring vital.

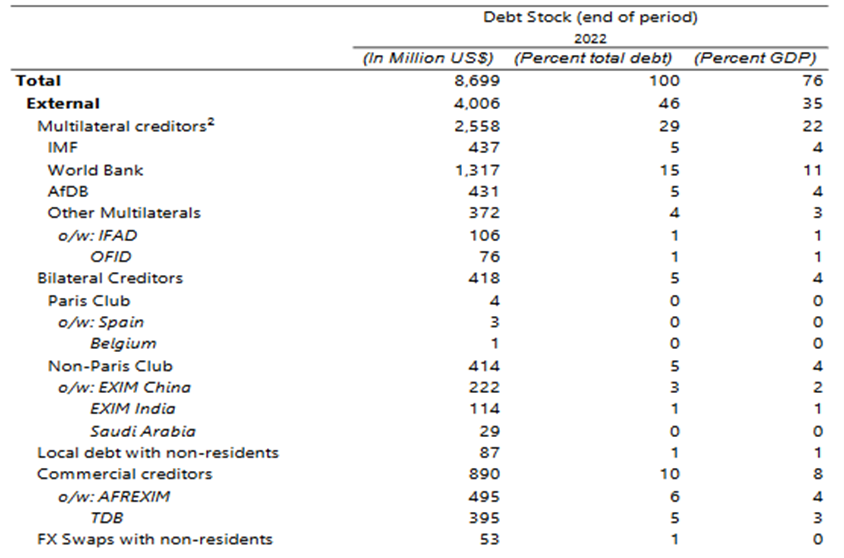

As Figure 2 shows, of the $4 billion in Malawi’s total external public debt, $2.6 billion is owed to multilateral creditors. The World Bank is the largest creditor, with $1,3 billion, or 33 percent of Malawi’s total external public debt. This means that only about one-third of Malawi’s external public debt stock is under negotiation, with $1 billion to commercial creditors (mostly to African Export-Import Bank and Trade & Development Bank) and $437 million to bilateral creditors (mostly China and Saudi Arabia).

Figure 2: Malawi, Decomposition of External Public Debt by Creditor, 2022

Malawi’s current debt restructuring

The IMF expects that between 2023-2027, Malawi will need $1.6 billion to close its external financing gap, of which $987 million should be financed by debt relief, as shown in Figure 3. As multilateral creditors are excluded from absorbing any losses, debt relief will be provided mostly by commercial creditors ($887 million) and official bilateral creditors ($99 million). This debt relief constitutes an 86 percent haircut on commercial creditors’ nominal claims and 25 percent over official bilateral nominal claims. China and India have provided financial assurances for the IMF program, and Malawi is in negotiations with its commercial creditors – to whom Malawi is on arrears.

Figure 3: Malawi, External Financing Gap, 2023-2027

| 2023-24 | 2023-27 | |||

| US$ mn | % total | US$ mn | % total | |

| Financing gap | 1,056 | 100 | 1,599 | 100 |

| IMF ECF | 53 | 5 | 178 | 11 |

| Grants/loans (disbursed in 2023) | 106 | 10 | 106 | 7 |

| Prospective grants/loans | 221 | 21 | 329 | 21 |

| Prospective debt relief | 676 | 64 | 987 | 62 |

| Official Bilateral | 39 | 4 | 99 | 6 |

| Commercial | 636 | 60 | 887 | 55 |

However, even if Malawi receives an almost complete debt write-off from commercial creditors, it would still not be sufficient to eradicate the risks of debt distress. As per projections from the IMF, following the implementation of the program, Malawi is still expected to face a moderate risk of debt distress. Malawi’s government has very little leeway to spend in key priority areas or absorb unexpected shocks without returning to debt distress. Implementing Malawi’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) under the Paris Agreement would cost an additional $900 million per year (about 8 percent of their GDP), not to mention the financing needed to achieve the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Moreover, the intensification of climate change – which Malawi has not significantly contributed to – and more frequent climate disasters could further jeopardize Malawi’s debt sustainability and development trajectory.

But as the IMF points out, Malawi has “no buffer of restructurable debt,” as in 2025, it is projected that 90 percent of the country’s total external debt will be owed to MDBs. This means that, if Malawi returns to debt distress in the future, it will not be able to restructure its debt at all.

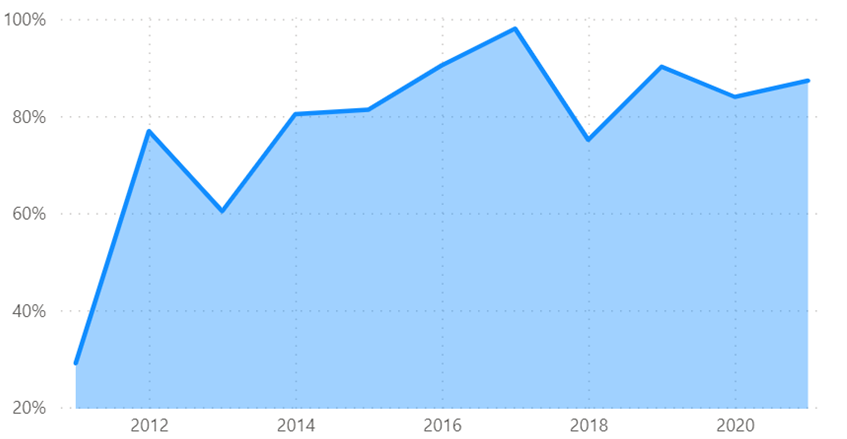

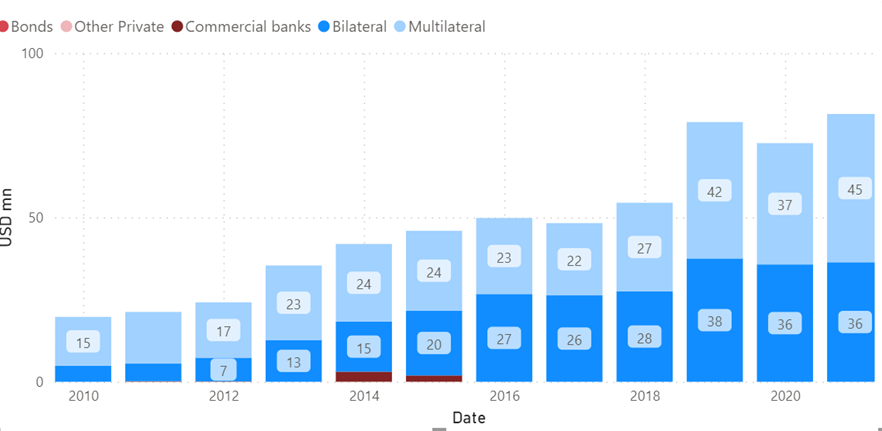

The resistance to include MDB claims in debt restructuring is understandable, given that, as shown in Figure 4, considering all creditors, over 80 percent of all PPG external debt disbursements come from MDBs since 2014.

Figure 4: Malawi, Disbursement from Multilateral Creditors as Share of Total Public and Public Guaranteed External Debt Disbursements, 2012-2021

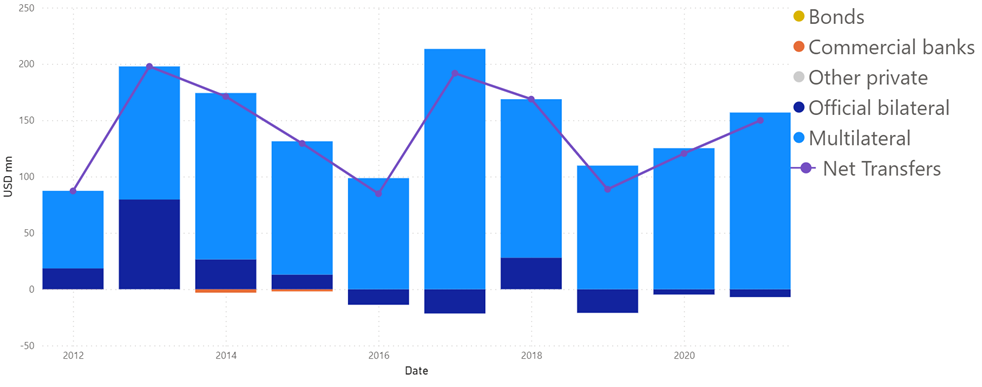

Moreover, MDBs are the only creditor providing a positive net transfer (PPG external debt disbursements being higher than amortization and interest payments), as shown in Figure 5. However, despite these consistently positive net transfers from MDBs, their scale is considerably small when compared to the country’s financing needs. For perspective, while MDBs’ net transfers amounted to $157 million in 2021 (slightly higher than in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), Malawi faced a current account deficit 10 times greater in the same year, reaching $1.54 billion. Moreover, the central government’s financing requirements stood at 9 percent of GDP in 2022, approximately $1 billion. Adding to this, the country urgently needs to increase its climate investments by at least $900 million per year. It is evident that the current financing levels from multilateral creditors fall significantly short of what Malawi requires to meet its developmental and climate goals.

Figure 5: Malawi, Net transfers (+Disbursement- Amortization -Interest), Public And Public Guaranteed External Debt, 2012-2021

Added to that, currently, most of Malawi’s external debt service is paid to MDBs, as seen in Figure 6. Missing any debt service payments to the MDBs would jeopardize Malawi’s only source of external financing. Although Malawi’s external PPG debt service is relatively small compared to the country’s overall external financing needs, these payments continued over the course of serious public emergencies, including the COVID-19 pandemic, and outbreak of cholera and Cyclone Fred. Given its depleted foreign reserves, the country is facing multiple shortages, including fuel and other essential goods like fertilizers, food and medicine.

Figure 6: Malawi, Public and Public Guaranteed External Debt Service, 2010-2022

Supporting Malawi’s path towards sustainable development requires substantial additional external resources. Debt restructuring with all external creditors should be the first step, but this must be coupled with aid and grants, concessional finance and more access to exports. Relying on partial debt restructuring and the fiscal adjustments – as recommended by the IMF – will be insufficient to achieve meaningful debt sustainability and put the country on the path to sustainable development.

External support will be paramount for Malawi – as for many other developing countries – and relying on fiscal adjustment will not only be insufficient to boost economic development, but can be counterproductive and accentuate inequalities. Poverty incidence in Malawi is the highest on the African continent, and 70 percent of its almost 20 million people live below the poverty line of $2.15 a day. Moreover, food insecurity is increasing and it is estimated that 22 percent of the population will face hunger during the current lean season – compared to 15 percent in the past year.

While acknowledging the severe poverty rates in Malawi, the IMF envisions an increase in government revenue by 5 percentage points of GDP over five years through enhanced taxation, including proposals like higher fuel taxes. However, this approach demands careful consideration due to potential inflationary impacts, particularly on transportation and the industrial sector, and the potential burden on the most vulnerable populations. The limited scope for raising domestic revenues underscores the urgency for Malawi to secure additional debt relief and external resources.

Key lessons

Malawi’s journey through its current debt crisis is emblematic of the broader challenges faced by developing countries in navigating global financial structures that reinforce inequalities. The country’s limited ability to negotiate a significant portion of its external debt, primarily due to the exclusion of claims from MDBs, starkly highlights the shortcomings of the existing debt relief frameworks. The policy option of excluding MDBs from providing debt relief not only undermines the effectiveness of debt restructuring efforts, but also jeopardizes the possibility that countries chart a path towards sustainable development. Moreover, the policy decision within the Common Framework to exclude MDB debt relief by default effectively reduces the pool of eligible countries that can seek debt treatment, illustrating a serious flaw in the international financial architecture.

The case of Malawi also brings to light the broader implications of current fiscal policies and their socio-economic impact. With a substantial segment of the population living in poverty and facing increasing food insecurity, there is a critical need for external support that goes beyond debt restructuring. It is paramount that developing countries receive a comprehensive package of aid, grants, concessional finance and Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), as well as increased market access for exports. Moreover, proposed fiscal adjustments risk deepening inequality and fueling inflation, adversely affecting key sectors, such as transportation and industry, and impacting the broader economy.

Moving forward, it is essential to recognize that the path to sustainable development and economic recovery for countries like Malawi requires not just bare-minimum debt relief but a holistic approach that considers all aspects of their economic and social realities. This necessitates a concerted effort from the international community to provide support that is both substantial and tailored to the unique challenges faced by each nation. Only through such comprehensive and tailored approaches can nations like Malawi overcome debt distress and chart a course towards lasting economic resilience and social prosperity.

Malawi, like many other developing nations, is at a critical juncture where environmental sustainability and economic development must be considered jointly. The country faces the dual challenge of managing its debt, while also needing to invest greatly in green technologies and sustainable practices to mitigate the impacts of climate change, to which it is particularly vulnerable. A holistic approach is crucial for turning the tide of the crisis and setting Malawi on a path to recovery and sustainable growth.