A new report by the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive (DRGR) Project explains why MDBs must be included in debt relief efforts, estimates their fair share of the burden and explores policy alternatives to preserve their high credit ratings.

by Marina Zucker-Marques

With the worsening debt situation in developing countries, the ongoing debt relief negotiations within the Group of 20 (G20) Common Framework have been disappointing. Among many issues delaying debt negotiations (like domestic debt restructuring, sharing information on debt sustainability analysis and debt carrying capacity), the question of whether multilateral development banks (MDBs) should participate in debt relief efforts has proven particularly contentious. Although the G20 has explicitly called for MDBs to develop options to share the burden of debt relief efforts, concrete and systemic plans are yet to be materialized.

A new report by the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive (DRGR) Project explains why MDBs must be included in debt relief efforts, estimates their fair share of the burden and explores policy alternatives to preserve their high credit ratings.

Why should MDBs be involved in debt relief?

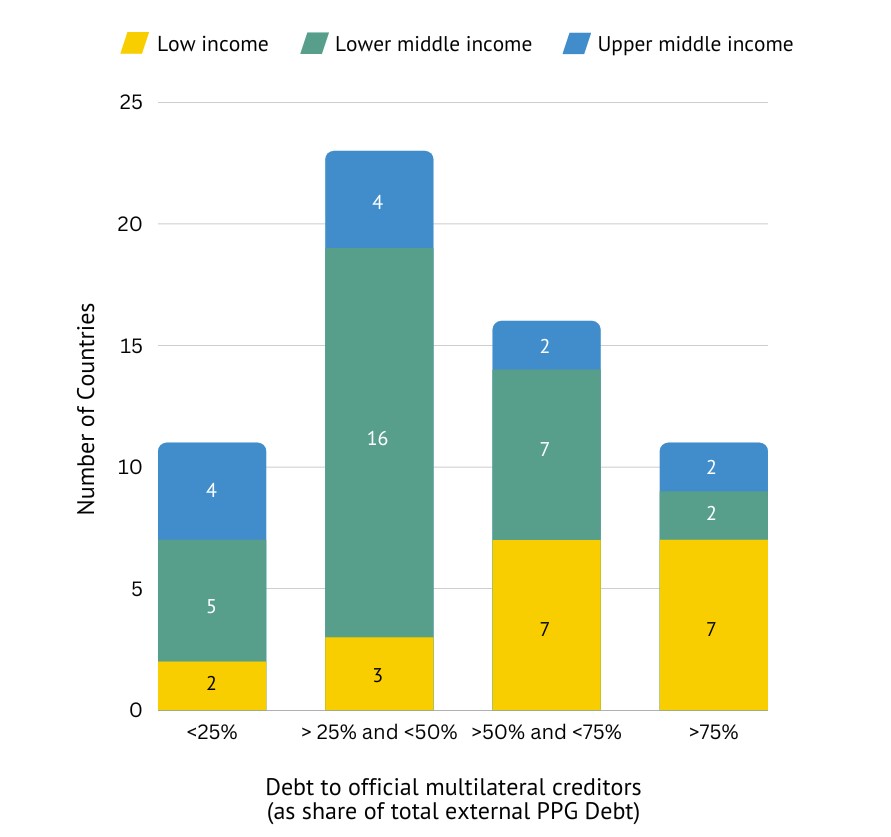

First and foremost, MDBs are important creditors to countries in need of debt restructuring. The DRGR Project has identified 61 countries that need imminent attention, termed New Common Framework (NCF) countries. As Figure 1 shows, for 16 NCF countries, exposure to official multilateral creditors is between 50 percent and 75 percent of their total external Public and Publicly Guaranteed (PPG) debt. And for 11 NCF countries, exposure is above 75 percent. Hence, if MDBs are not involved in debt relief efforts, countries will not have enough debt restructured to significantly increase their fiscal space. Given the higher exposure of low-income countries (LICs) to MDB lending (Figure 1, yellow label), excluding MDBs from debt renegotiation would disproportionally affect the poorest nations.

Figure 1: Debt Stock Exposure of NCF Countries to Official Multilateral Creditors by Income Group as Share of Total External PPG Outstanding Debt

Additionally, participating in debt relief efforts would reinforce the core mandate of the MDBs, which is to promote economic development and poverty reduction, as debt relief would increase the ability of governments to invest in priority areas.

Thirdly, MDB participation resonates with the “fair burden sharing” principle of debt negotiation and would ease the perception of inequity among creditors. Importantly, their participation could also help disentangle negotiations that are currently locked at a standstill.

Finally, abstaining from debt relief efforts would only prolong the debt crisis in the Global South, which would be costly for the MDBs, given the concessional nature of their lending. As the debt crisis is becoming widespread, MDBs are spending more and more on grants connected to debt distress indicators. Take the World Bank concessional arm (the International Development Association, IDA) as an example: According to our estimate, World Bank IDA grants based on debt sustainability criteria grew from $600 million to $4.9 billion (or from 8 percent to 36 percent of their commitments) between 2012-2021 for a group of countries only eligible to borrow from IDA. Considering these costs, it is in the best interest of MDBs to speed up debt relief negotiations and rebalance the business model of their concessional arm.

How much would debt relief cost MDBs?

Defining the burden sharing among creditors during a debt relief process is a highly complex exercise. To account for an equitable distribution of losses among creditors, it is crucial to consider the incorporation of default risks in pricing of private sector lending practices, as well as the distinct level of conditionalities offered by official creditors. For this reason, the DRGR report considers a “fair” comparability of treatment (CoT) rule, which incorporates borrowing costs by creditor classes.

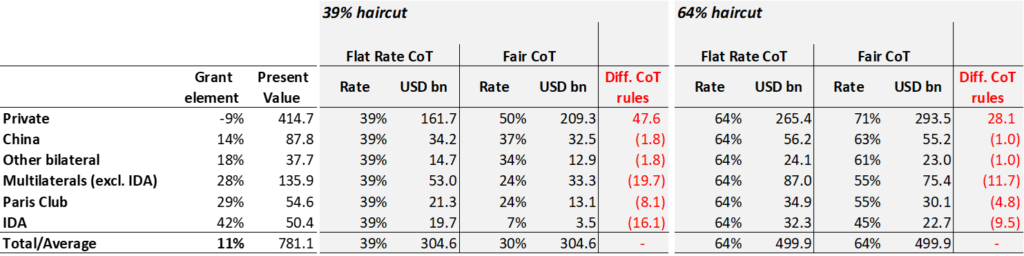

Table 1 estimates the burden share among six creditor classes if the external PPG debt of NCF countries is restructured. Our empirical exercise compares two approaches to comparability of tretment: the “fair” rule that incorporates borrowing costs and the “flat rate” that applies the same present value discount to all creditors. Moreover, we provide two scenarios of debt reduction: First, a historical average of 39 percent and, second, 64 percent which is same reduction adopted during the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative.

According to the “fair” rule, official creditors would contribute with a relatively smaller haircut compared to the “flat rate” rule. For instance, under the “fair” rule with a 39 percent debt reduction for NCF countries (table 1, middle columns), MDBs (excluding IDA) would contribute with a 24 percent haircut (or a total of $33.3 billion losses) and IDA with a 7 percent haircut (or $3.5 billion). This means that by adopting the “fair” CoT, MDBs (excluding IDA) would reduce their contribution to debt relief by $19.7 billion and IDA, by $16.1 billion.

Under this “fair” rule, China’s contributions to debt relief would also decline from $34.2 billion to $32.5 billion, for another bilateral official from $14.7 billion to $12.9 billion, as well as for Paris Club countries, at $21.3 billion to $13.1 billion. To achieve the required overall debt reduction, the haircut from private lenders would increase from 39 percent to 50 percent, or from $161.7 billion to $209.3 billion.

Table 1: NCF (61) Countries, Inter-creditor Burden Sharing, According to Distinct Comparability of Treatment Rules and Haircut Levels

As the right side of table 1 shows, If NCF countries receive a HIPC-like reduction of 64 percent of their global debt (in terms of present value), the efforts from IDA following the “fair” CoT would account for $22.7 billion ($9.5 billion less than with the “flat rate” CoT), which would correspond to a 45 percent haircut instead of 64 percent. For MDBs (excluding IDA), the contribution would be $75.4 billion (55 percent haircut) and $11.7 billion lower compared to the “flat rate” rule. The increase from the 39 percent case is substantially higher for IDA, because as the overall debt reduction increases, efforts from other creditors need to increase to avoid leaving the least concessional creditor to completely write off their debt.

How can MDBs preserve their credit ratings?

MDB lending is crucial to supporting green and inclusive development. MDBs can finance their clients with low-interest rates because of their high credit rating, which should be preserved regardless of MDB’s debt relief efforts.

MDB shareholders could consider three possible policy alternatives to compensate for any losses while giving countries a fresh start at financing a fiscally sound future.

First, donor countries can make a significant impact by contributing to new rounds of debt relief through mechanisms like the Debt Relief Trust Fund, which would pool resources from international financial institutions and donors, allowing for more comprehensive debt relief efforts. Moreover, integrating debt relief as a regular component of concessional finance policies is vital. For instance, allocating a dedicated portion of funding in each IDA replenishment for debt relief efforts can ensure a sustained focus on reducing the debt burden of developing nations.

A second avenue to explore is the potential increase in MDB equity. By bolstering the equity of these institutions, a portion of precautionary balances could be made available for utilization in debt relief endeavors. This approach would not only provide additional resources for relief efforts, but also safeguard the institutions’ credit ratings

Finally, the revival of international financial transaction tax (IFTT) discussions is worth considering. Although challenging from a political perspective, a well-designed IFTT applied to various financial transactions could yield substantial revenues. Redirecting these funds towards MDBs would not only support debt relief but also contribute to broader development goals.

In short, including MDBs in debt relief is crucial to effectively addressing the mounting debt crisis in the Global South. Equitable burden-sharing among creditors is imperative to foster a fair and transparent process that encourages the participation of all stakeholders. While there are costs associated with providing debt relief, it would be a prudent investment for the long-term stability and development of debt-vulnerable nations. Implementing policy options to support MDBs in shouldering these costs will be key to ensuring a sustainable future for all.